The Age of Rights?

World War II brought a new awareness of human rights around the world. After the horrors of the Holocaust came to full light, few people could deny the dangers of racism. The anti-colonial movement was growing stronger around the world, and with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 by the newly formed United Nations, many turned their attention to the rights of colonized people globally. In Africa, Asia, and the Americas, liberation movements helped bring the plight of millions under European colonialism to public attention.

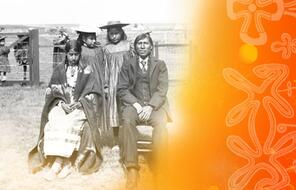

In Canada, the experience of World War II left many troubled by two issues in particular: people were alarmed not only by German atrocities but also by new personal awareness of the unresolved injustices committed against Indigenous Peoples. Many indigenous soldiers had volunteered—they did not have to be drafted—to fight in the war for freedom from oppression, racism, and discrimination. This fact shed a new light on the dark history of Canadian-Indigenous relations. “Aboriginal soldiers returning to civilian life,” wrote Alan McMillan and Eldon Yellowhorn, “brought with them new ideas about their relationship with their country: their experience convinced them that unfinished business existed between Canada and the Aboriginal population.” 1

Shortly after World War II, a special joint committee of the House of Commons and the Senate began to review the situation in Canada’s 78 existing residential schools and presented its findings in 1948. It had to face a new reality: the indigenous population was growing. 2 With costs increasing, the 1948 report called for the abolition of the residential schools once and for all and for the integration of indigenous people into regular provincial schools.For the next decades, integration became a key policy promoted by the government.

Indigenous leaders were skeptical about the idea of integration. Chief Dan George said in or around 1972, “You talk big words of integration in the schools. Does it really exist? Can we talk of integration until there is social integration . . . unless there is integration of hearts and minds you have only a physical presence . . . and the walls are as high as the mountain range.” 3

Indeed, critics were quick to point out that while integration sounded better than the idea of assimilation on paper, the two were quite similar in practice. A policy of integration was just as likely to ignore indigenous traditions and cultures and force Indigenous Peoples to accept European norms, values, and languages. One significant difference stood out: parents and other members of the community were now invited to take part in the education of their children. In that sense, the government replaced the aggressive assimilation policy discussed previously with a softer kind of assimilation; however, both approaches had the same goal. 4 Even with the changes, the residential school system lingered, half-alive, half-dead. It wasn’t until 1969 that the government withdrew the schools from the churches’ operational authority. It then took an additional 25 years for the last residential school to close.

The period surrounding Canada’s 100th anniversary, 1967, proved fateful. When Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau came to power in 1968, he ordered Jean Chrétien, his Minister of Indian Affairs and a future prime minister, to review the Indian Act. The result was the 1969 White Paper (a policy statement). 5

Ignoring other suggestions that focused on addressing the legacy of colonialism by giving special attention to Indigenous Peoples as a group, the government was prepared to launch yet another policy of full integration. 6 Despite the (legal) language of equality, to indigenous leaders this policy read every bit like the old programs for assimilation. The 1969 White Paper recommended the abolition of the Status Indian designation and—gradually—all government protections and provisions for the Indigenous Peoples, including the Indian Act, treaties, and other indigenous rights. The document stated, “The government believes that services should be available on an equitable basis, except for temporary differentiation based on need. Services ought not to flow from separate agencies established to serve particular groups, especially not to groups that are identified ethnically. . . . All Indians should have access to all programs and services of all levels of government equally with other Canadians. . . . ” 7 For a short while, Prime Minister Trudeau embraced the vision behind the White Paper with great enthusiasm. 8

- 1Alan D. McMillan and Eldon Yellowhorn, First Peoples in Canada (Madeira Park, BC: Douglas and McIntyre, 2013), 322.

- 2John Milloy, “Indian Act Colonialism: A Century of Dishonour, 1869-1969,” National Centre for First Nations Governance, 2008, accessed May 8, 2015.

- 3Chief Dan George, from his soliloquy “A Talk to Teachers,” quoted in Verna J. Kirkness, “Aboriginal Education in Canada: A Retrospective and a Prospective,” Journal of American Indian Education 39 (1999), 7.

- 4Eric Taylor Woods, The Anglican Church of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools: A Meaning-Centred Analysis of the Long Road to Apology (dissertation, London School of Economics, 2012), 63–64.

- 5For document’s full text, see Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy (The White Paper, 1969), Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development website.

- 6Two years earlier, anthropologist Harry B. Hawthorn had published a critical report that recommended the abolition of the residential schools and the designation of the Indigenous Peoples as “citizens plus” to address past injustices. See Harry B. Hawthorn, A Survey of the Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political, Educational Needs and Policies, Parts 1 and 2, 1966–67, Indian Affairs and Northern Development website, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 7Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy (The White Paper, 1969).

- 8Eric Taylor Woods, The Anglican Church of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, 70.