Colonial Power Struggle

War and political changes also contributed to the destruction of indigenous ways, livelihoods, and physical existence. France and Great Britain, the largest colonial powers in the world, began to clash openly in 1754 over several areas of control, including North America. Two years later, they declared war, and each recruited First Nations to fight on their side. In 1763, at the end of what the British called the Seven Years’ War (known as the War of Conquest in French Canada), the Treaty of Paris ceded most of the French territories in North America to Great Britain.

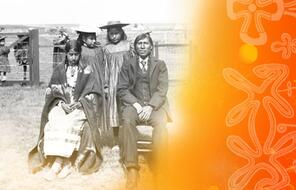

Early European perceptions of Indigenous Peoples were often reflective of the relatively peaceful and mutually beneficial relationship between the two groups. Indigenous nations, particularly those of the Great Lakes region, had a long and close relationship with the French. Thus, the war and the conquest of the French territories by the British created deep tensions around the issue of indigenous sovereignty and the integrity of their way of life.

Minavavana, a Chippewa leader in French Canada, responded to the victory of the British in the war against the French as follows, insisting on the rights of his people:

Englishman, although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods and mountains were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance, and we will part with them to none. Your nation supposes that we, like the white people, cannot live without bread and pork and beef! But you ought to know that He, the Great Spirit and master of Life, has provided food for us in these spacious lakes and on these woody mountains. 1

In 1763, at the official end of the war, the victorious King George III of Britain issued a Royal Proclamation meant to establish good relations between the First Nations and the settlers. It was an attempt to address the concerns of indigenous people such as Minavavana; it clearly defined the areas belonging to the Indigenous Peoples, territories where no private squatting, settlement, or sales were permitted. 2 The Royal Proclamation was the first public British acknowledgement of the pre-existing rights of First Nations to their lands, and its unique language also recognized the First Peoples as nations. This set the stage for a series of treaties signed between the First Peoples and the British Crown on equal footing: nation-to-nation treaties. To this day, the document serves as an official recognition of the rights of First Nations to their land and of the “sovereignty of the Indian nations.” 3

- 1Minavavana, “We are not your slaves,” National Humanities Center, “Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690–1763,” accessed September 10, 2014.

- 2Ian L. Getty and Antoine S. Lussier, eds., As Long as the Sun Shines and Water Flows: A Reader in Canadian Native Studies (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2000), 7.

- 3Ian L. Getty and Antoine S. Lussier, eds., As Long as the Sun Shines and Water Flows: A Reader in Canadian Native Studies (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2000), xi.