Colonization

When the European powers set their sights on North America, some three hundred years after the so-called discovery of the continent (which for them was the “New World”), it became a location for French and British settlements. The process of assuming control of someone else’s territory and applying one’s own systems of law, government, and religion is called colonization. Indeed, prior to the 1800s, settling the land was not the first priority. The Europeans exchanged goods for furs and meat; they also went on fishing and whaling expeditions before returning to Europe with fish and oil. With the exception of trading posts, primarily along the St. Lawrence River and the coastline, the colonial powers did not attempt to settle the country on a large scale. Between the scattered European settlements, indigenous nations reigned.

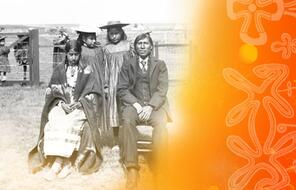

Europeans and Indigenous Peoples of Canada interacted through the fur trade for almost 300 years. This photo is from the 1950s, when the extensiveness of the trade network had much declined from its peak in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

At its peak, the fur trade, which lasted almost 300 years, involved thousands of hunters, trappers, processors, guides, indigenous traders (i.e., Cree and Métis), and (primarily) Hudson’s Bay Company merchants. Indigenous people in Canada met their European counterparts on more or less equal terms with mutual benefits. Agreements between the settlers and Indigenous Peoples guaranteed the right of the latter to use and protect their land “as long as the sun shines, the river flows, and the grass grows”—a phrase enshrined in a series of nation-to-nation alliances and treaties. 1

But with the introduction of new, cheaper fabrics and changes in European fashion, the fur trade began a steady decline. Moreover, with the European expansion to the West and the discovery of gold, the delicate balance between the two communities was disrupted. As one historian wrote, “Until the gold rush of 1858, fur trading had been the dominant industry. . . . With the rush, mining became the predominant economic activity: at its peak, there were as many as 20,000 prospectors. Coal mining, as well as forestry and fishing, also emerged during this period, but none rivaled gold in importance [until the mid-1860s].” 2 As the Prairies were settled, they became the breadbasket for all of Canada and a growing market for eastern Canada’s industries. In this new economy, there was a smaller role for Cree and Métis traders. Thousands of communities that were touched by the trade with Europe suffered decline too, a process that was exacerbated by the settlers’ increasing encroachment on the land, resources, and ways of life of the Indigenous Peoples of North America.

- 1 José António Brandão, “The Covenant Chain,” Encyclopedia of New York State online, accessed November 10, 2014,. These nation-to-nation con- tracts and agreements go back to the early encounters between European settlers and local nations, when they entered into agreements for the benefit of both sides. Those agreements continued with the Royal Proclamation of 1796 (in which the Crown acknowledged the nationhood and land rights of the Indigenous Peoples) and the official treaties between First Nations, the British Crown, and the Canadian government after federation. Numerous court and government decisions routinely ratified these treaties since.

- 2“Canadian Confederation,” Library and Archives Canada website, accessed September 10, 2014.