The Government’s “Statement of Reconciliation”

By the 1980s, it had become clear that the effects of the residential schools were far greater and longer-lasting than most Canadians cared to admit. Historian John Milloy offers the following assessment:

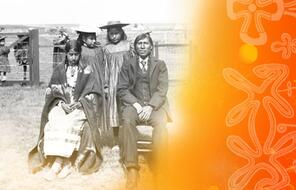

Through the 1960s and 1970s, the evidence of the destructive impact of the schools, of their institutional parenting of children, and their trans-generational effects accumulated in Departmental files. . . . The schools were factories of disability and deviance more than they were halls of learning. 1

Tensions between the government and Indigenous Peoples were rising. In 1988, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations George Erasmus warned the Canadian government that ignoring the rights and land claims of Indigenous Peoples could lead to violence: “We want to let you know,” he said, “that you are dealing with fire. We say, Canada, deal with us today because our militant leaders are already born. We cannot promise that you are going to like the kind of violent political action we can just about guarantee the next generation is going to bring to our reserves.” 2

After years of criticism, the federal government faced several questions. What was its moral and financial obligation to the Indigenous Peoples of Canada whose sons and daughters were severed from their families at a young age? What could it do to respond to the critics who pointed to a long history of marginalization, discrimination, and dispossession? And what was the price of doing nothing?

After a series of confrontations, some quite violent, the government decided to act. In August of 1991, it set up the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) to address growing indigenous discontent. The commission spent five years holding public hearings, visiting communities, consulting with indigenous experts, and conducting research. At the end of these five years, in 1996, the commission produced a report evaluating the relationship among the indigenous population, the federal government, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, and Canada as a whole. 3 The report concluded that it was necessary to change the relationship between the communities from the ground up, to develop one “on a new footing of mutual recognition and respect, sharing and responsibility.” 4

The RCAP created an extensive 20-year plan of changes related to treaties, employment, education, health care, women’s rights, and much more. The report, highly critical of the treatment of indigenous children in residential schools, triggered the first public apology from the government. On January 8, 1998, Jane Stewart, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, delivered a written apology to Phil Fontaine, the then Chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN). The government also set a fund of $350 million “for community-based healing as a first step to deal with the legacy of physical and sexual abuse at residential schools” and laid plans for community development and strengthening indigenous governance. 5

But for many indigenous activists and Indian Residential Schools survivors, the statement was too little, too late. Many former students (or survivors) of the residential schools sought a more comprehensive and just settlement, one that would include an apology from the head of state.

Frustrated by the government’s response, in 2005, Phil Fontaine, in his role as National Chief of the AFN, launched a massive lawsuit on behalf of the “First Nations, Survivor, Deceased, and Family Class.” 6 Chief Fontaine explained: “We would rather negotiate than litigate, but we feel compelled to exercise all our options. Each day we lose another survivor. Each day someone passes on without having achieved any sense of justice or healing or redress.” 7 The First Nations, Survivor, Deceased and Family Class agreed to settle the suit out of court in 2006, signing the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) with representatives of the federal government, the survivors, the AFN, and the churches. It went into effect in 2007.

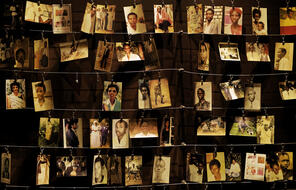

As part of this agreement, the government was required to set aside some $2 billion for about 86,000 surviving students (out of an estimated 150,000 students altogether), many of them forced to attend residential schools. 8 Each qualified person was to receive $10,000 for attending such a school, plus $3,000 for each year at the school (the Common Experience Payment ). 9 In a separate process (the Independent Assessment Process ), survivors who suffered abuse were to be “scored” according to the abuse they endured and would receive additional compensation. 10

- 1John Milloy, “Indian Act Colonialism.”

- 2“Standoff at Oka,” CBC website, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 3See Ronald Niezen, Truth and Indignation, Kindle Locations 1084–1087.

- 4“Highlights from the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples,” Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada website, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 5“Notes for an Address by the Honourable Jane Stewart Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development on the occasion of the unveiling of Gathering Strength—Canada’s Aboriginal Action Plan,” Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada website, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 6“AFN National Chief Files Class Action Claim Against the Government of Canada for Residential Schools Policy,” MediaNet, August 3, 2005, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 7“AFN National Chief Files Class Action Claim Against the Government of Canada for Residential Schools Policy,” MediaNet, August 3, 2005, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 8“A history of residential schools in Canada,” last updated on January 7, 2014.

- Common Experience PaymentCommon Experience Payment: The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement set aside some $2 billion in monetary compensation for about 86,000 surviving students (out of roughly 150,000 students altogether). These funds were distributed through the Common Experience Payment, which provided each qualified person $10,000 for attending such a school, plus $3,000 for each year at the school.

- 9"A history of residential schools in Canada,” last updated on January 7, 2014.

- Independent Assessment ProcessIndependent Assessment Process: The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement allotted monetary compensation to former students of the residential schools and set aside some $2 billion for about 86,000 surviving students (out of roughly 150,000 students altogether). A portion of these funds went toward the Independent Assessment Process, a separate process through which survivors who suffered abuse received additional compensation.

- 10 For more on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s mandate, see Schedule “N” of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Reconciliation Commission of Canada website, accessed February 6, 2015.