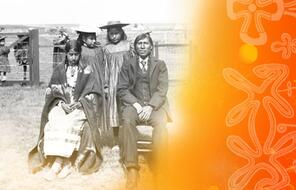

The Invention of the “Indian”

"The Indian began as a White man’s mistake, and became a White man’s fantasy. Through the prism of White hopes, fears and prejudices, indigenous Americans would be seen to have lost contact with reality and to have become 'Indians': that is, anything non-Natives wanted them to be." –Daniel Francis, historian

Since the classical age, when the Greek and Roman cultures flourished, Europeans have been fascinated by people who lived elsewhere: populations unknown outside Europe. First the Europeans called them barbaric; later, when Europe became Christian, they were referred to as pagans; later still, Europeans called them uncivilized. With little communication and minimal travel options, news about Asians, Africans, and later the people of the Americas travelled slowly. Where source information lagged or lacked, the European imagination filled in the gaps with misconceptions and stereotypes. Soon the language describing non-Europeans began to take both negative and romantic tones, reflecting Europeans’ anxieties about the people who lived elsewhere.

When the first European explorers landed in the Americas in 1492 with Christopher Columbus, they referred to the entire indigenous population on the continent as “Indians” because they believed that they had arrived in India. Although it quickly became clear that this was not the case, the name stuck. One of the first acts of the European colonization of the Americas, then, was not the taking of indigenous lands for settlement—it was an act of naming or, more accurately, misnaming. The Europeans imposed this single inaccurate label upon a variety of different peoples. (That said, Columbus’s first encounter with the “New World” did not involve just words; it was extremely violent and included forced servitude, kidnapping, and mass killings.)

In writing about the new people they met, the Europeans assumed a very clear hierarchy between the superior West and the inferior “New World.” To begin with, the Europeans, who had developed a written culture early on, tended to view the history and culture of peoples without a written language as inferior. Since indigenous traditions were not recorded in writing, they were deemed unreliable, mythological, a fiction. 1 Similarly, Europeans dismissed the spirituality of Indigenous Peoples as superstitious and their understanding of the world and its creation as a myth.

Some European writers saw Indigenous Peoples as noble, exotic figures. But this image was a myth in itself; the noble, free “pre-social” being was largely a figment of the imagination of Englishmen and Frenchmen who romanticized a life without the constraints and corruption in their civilizations. Pushed to the extreme, this view of Indigenous Peoples living a primitive, pre-civilized life implies that they also behaved like animals. Consider, for example, what the French priest Louis Hennepin had to say about the First Peoples he encountered in 1683:

The Indians trouble themselves very little with our civilities. . . . Men and women hide only their private parts. . . . They eat in a snuffling way and puffing like animals. . . . In fine, they put no restraint on their actions, and follow simply the animals. 2

Other Europeans, including many missionaries who worked in colonial Canada, viewed indigenous populations through the lens of religion. To them, these “children of nature” were a living example of the Biblical story of Adam and Eve. In their Garden of Eden, they lived in blissful, child-like ignorance and sin. 3 Some Christians called them noble savages and believed that with time and the proper religious environment, the “primitive Indian” could achieve civilization just like the modern European man. 4

Such Europeans further believed that the differences between the cultures were not innate, for all humans were alike in the eyes of God. As one early North American missionary told the indigenous people he encountered, the Christian God “is a God that will be found of them that seek him with all their hearts; and hears the prayers of all men, Indian as well as English.” 5 This idea was a leading mindset behind the establishment of the religious residential schools. 6 So was the idea of a child-like Indian: these people were to become wards of the state for their own protection and so that they would be civilized and, in the long run, become part of the European Canadian society.

But for some, the difference between the unreligious pagan and the Christian was a vast, even impossible gap to bridge. By the middle of the nineteenth century, impatience with the progress of the civilizing process led to frustration and to yet another stereotype. Now some came to see these people not only as savages but also as “wretched Indians”: cunning, vile, detestable beings. 7 By the end of the nineteenth century, Canadian officials had embraced a similar idea and started a campaign to assimilate the Indian using the residential schools.

- colonizationcolonization: This term refers to a situation in which one nation takes over and settles a geographic area populated by other, indigenous peoples. For example, the area now known as North America was colonized by Europeans from the sixteenth century onward at the expense of the indigenous populations that had been living there for millennia.

- 1As one scholar put it: “Because the [Aboriginal] had no written records when the first white man reached this continent, he was dismissed by the white man as having no past.” George F. G. Stanley, “As Long as the Sun Shines and Water Flows: A Historical Comment,” As Long as the Sun Shines and Water Flows: A Reader in Canadian Native Studies, ed. Ian L. Getty and Antoine S. Lussier (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2000), 1–2.

- 2Louis Hennepin, A Description of Louisiana by Father Louis Hennepin, Recollect Missionary, trans. John Gilmary Shea (New York: John G. Shea, 1880).

- 3The image of the “noble savage” persists under a very modern guise: the “ecologically noble savage,” which suggests that indigenous life was not only more peaceful but also much more ecologically sustainable and harmonious than modern society allows. See Shepard Krech, The Ecological Indian: Myth and History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999), 19–23.

- 4Carol L. Higham, Noble, Wretched, and Redeemable: Protestant Missionaries to the Indians in Canada and the United States, 1820–1900 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000), 33.

- 5Martin Moore, Memoirs of the life and character of Rev. John Eliot [1904-1690] (Boston: Flag & Gould, 1822), 25.

- 6Carol L. Higham, Noble, Wretched, and Redeemable, 67–68.

- 7Carol L. Higham, Noble, Wretched, and Redeemable, 31–60.