Legislation for the Residential Schools

The assumption behind Davin’s proposal was that if indigenous children and youth were separated from their families and educated in the European tradition, they would abandon their traditional values, customs, and lifestyles. Moreover, when the students returned home, they would bring these Western ways to the other community members. For reference and aid, the government also turned to the various church denominations, which had already begun the process of creating missionary schools.

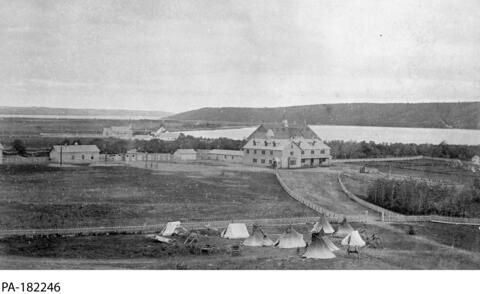

In this photograph, tipis stand just outside the fence of Fort Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School in 1895 in Lebret, Saskatchewan. The tipis likely belong to the First Nations families of children attending the school.

But until 1883, Canada did not have a residential school system. Rather, it had individual church-led initiatives to which the federal government provided grants. 1 Based on these pre-Confederation religious boarding schools, the government was to seek partnerships with representatives of the Anglican, Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, and other churches to operate the schools and to carry out this mission for the state. Religious instruction and discipline became the primary tool to “civilize” indigenous people and prepare them for life as mainstream European-Canadians.

To achieve this goal, Prime Minister Macdonald authorized the creation of new residential schools and granted government funds for those that were already in place. Macdonald, like others in the government administration, was very clear about the need to break the connection between the students and their communities: “When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with his parents who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write.” 2

Two models of schooling were pursued: industrial and residential schools. The industrial schools were to focus more on rudimentary farming skills and trades. Those were not boarding schools, although the students often lived in a separate building on site that served as a hostel. The residential schools were to be more academic, though they too offered training in farm work (for boys) and domestic skills (for girls). While a far cry from the boarding schools for Canada’s privileged youth, these offered full board for First Nations students, as they were government-funded. The reality of the Indian education model was not based on principles of schools or academic enrichment, however; rather, the system was founded on principles of “reformatories and jails established for the children of the urban poor.” 3

- 1Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012), 6.

- 2Quoted in Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012), 6.

- 3Quoted in Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012), 6.