Truth and Reconciliation

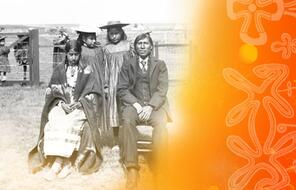

What action can bring closure to episodes of conflict and mass violation of human rights? What can help create goodwill and trust between groups in the aftermath of such tragic events? Because of the massive lawsuit it faced, the government was almost forced to focus on the Indian Residential Schools, and it set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 2008 to address those issues. So what is a truth and reconciliation commission? What are its goals?

Truth and reconciliation commissions have become commonplace since the 1970s. They reflect a global trend of paying more attention to mass violations of human rights. Most such commissions (if not all) focus on crimes carried out by a government against its own citizens. The Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission is part of a complicated series of reconciliation hearings and events. It is unique in that it does not signify or facilitate a transition from one regime to another. In that sense, it is part of what experts call restorative justice rather than transitional justice, a process that helps a country move from, say, a dictatorship to a democracy. 1

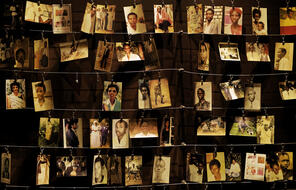

Truth and reconciliation commissions are often a way for perpetrators and victims to publicly acknowledge episodes of violence between them. Such commissions provide a space for former enemies to bridge their differences. 2 For the most part, they are designed to bring about processes of healing, processes that offer victims solace and reassurance that their trauma will not be repeated. 3 But in Canada, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was focused almost exclusively on victims and their experiences.

The Canadian TRC is not a court; it has no legal authority. 4 It doesn’t indict, charge, or convict, but rather serves to open discussion and develop relationships about the difficult subjects surrounding the residential schools experience. We need to remember that for years, survivors of the residential schools did not speak out about their childhood experiences. Many factors contributed to their silence. For survivors, these included the shame and stigma associated with violence and sexual abuse. But language plays a big role here, too—or, rather, the absence of language does. Many survivors could not find the words to describe their painful experiences in the Indian Residential Schools system. As a British Columbia judge said, “[O]ne is drawn to the conclusion that the unspeakable acts which were perpetrated on these young children were just that: at that time they were for the most part not spoken of.” 5

Since the beginning of its work in 2010, the commission has been collecting information about what was done to survivors in the residential schools and has worked to make this information public. From this process, the survivors receive public, communal acknowledgement and support for years of injustice and suffering. 6 Therefore, in many ways, the Canadian TRC facilitates the return and inclusion of survivors into the community, those former students whose secret and denied pains prevented them from partaking in day-to-day social activities. 7

But one of the most important roles the TRC took on, according to Commissioner Marie Wilson, was that of educating the Canadian public, which for many years was oblivious to the suffering of survivors. 8 If this educational goal is met with success, it will alter the ways in which Canadians think about their culture and history, challenging their identity as members of a community that knew no violence—a tolerant, pluralistic community. Such transformation, many believe, is the first step toward reconciliation between the two communities.

- 1“Transitional Justice” and “Restorative Justice,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy online. For an in-depth discussion of the relationship between the two concepts, see Kerry Clamp and Jonathan Doak, “More Than Words: Restorative Justice Concepts in Transitional Justice Settings,” International Criminal Law Review 12 (2012), 339–360.

- 2See G. G. J. Knoops, “Truth and reconciliation commission models and international tribunals: A comparison,” paper presented at “The Right to Self-Determination in International Law” symposium, September 29 – October 1, 2006, accessed September 11.

- 3Brian Rice and Anna Snyder, “Reconciliation in the Context of a Settler Society: Healing the Legacy of Colonialism in Canada,” From Truth to Reconciliation, 46, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 4See “Schedule N” of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada website accessed February 6, 2015.

- 5Ronald Niezen, Truth and Indignation, Kindle Locations 1514–1518.

- 6Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: ‘For the child taken, for the parent left behind’” United Nations Conference Room Paper, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada website, accessed February 6, 2015.

- 7For more on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s mandate, see Schedule “N” of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada website.

- 8“Canada’s Youth Face Legacy of Indian Residential Schools at ‘Education Day’ Event,” International Center for Transitional Justice website, accessed March 5, 2015.