“Until There Is Not a Single Indian in Canada”

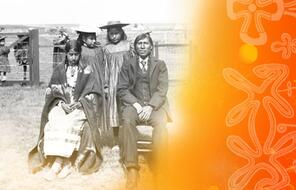

Duncan Campbell Scott was to run the residential school system at its peak— that is, between 1913 and 1932. Scott was what might be called an extreme assimilationist. As a career civil servant, he was involved in Aboriginal affairs throughout his career (he proposed several amendments to the Indian Act and negotiated one of the major treaties). More importantly, he oversaw the operation of the residential schools. Scott was an active official, and while he seems to have appreciated some elements of the indigenous cultures, he also contributed much to their destruction. 1 Moreover, in 1924 he proposed an amendment to the Indian Act that banned those under its jurisdiction from hiring lawyers (without the DIA’s approval) to represent them in land and rights claims. 2 For these and many other contributions, experts call Scott the “architect of Indian policies” during the first decades of the twentieth century. 3

In 1920, Scott also pushed for and passed an amendment to the Indian Act making school attendance compulsory for all First Nations children less than 15 years of age. As a result of the amendment, indigenous enrollment rose to about 17,000 in all schools and to more than 8,000 in residential schools by the end of his tenure. According to Scott’s reports, at this point, 75% of First Nations children were enrolled in some school, which he attributed to a growing motivation among them to take up Western education. Clearly, the fact that the education was now compulsory and that, since 1930, it included all children between the ages of 7 and 16 had something to do with these numbers. 4

While Scott did not think that education alone was sufficient for civilizing the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, he pushed heavily for it. When he mandated school attendance in 1920, he stated, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone. . . . Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.” 5 Because of his radical position, it is easy to understand why he is often associated with the saying “Kill the Indian, save the man.” 6 In the discussion about whether the Canadian assimilation policies and the Indian Residential Schools constitute genocide , this approach is often key evidence. Scott summarized the prevailing attitudes of Canadian officials: the First Peoples, despite many agreements with the Crown that guaranteed their independence, were to be eradicated as distinct nations and cultures.

By the turn of the twentieth century, there were 18 industrial and 36 residential schools; three decades later, at the peak of the system’s operation, there were 77 state-funded residential schools in Canada. 7 Shortly after, there were 80 schools, of which “over one-half—44—were under various Catholic orders, 21 under the Church of England (later the Anglican Church of Canada), 13 under the United Church, and 2 under the Presbyterians.” 8 Over the 150-year span of the Indian Residential Schools system , Canada saw close to 150 schools and 150,000 pupils.

Although Scott was proud of his work and the growing numbers of students in residential schools, things were not looking up. Numbers in schools, wrote Brian Titley, “did not automatically translate into numbers being assimilated. Undoubtedly, the school experience profoundly affected the outlook of young Indians . . . The vast majority remained distinctly Indian and only marginally in the workforce, if indeed at all. In terms of its objectives, then, the policy of educating the Indian children in segregated day and residential schools failed.” 9

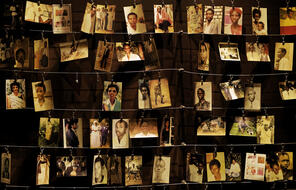

Beyond the failure of the schools with regard to their aims of assimilation, Scott was blamed for the neglect and death of many children. Dr. Bryce, as we have seen, found Scott’s penny-pinching to be the main obstacle in promoting basic reforms that could have saved many lives. But nobody listened to him. A defeated, aging man, Bryce published a pamphlet in 1922 called “The Story of a National Crime.” In it he argued that “Scott, in particular, had consistently failed to acknowledge and address native health needs.” 10 It is now estimated that at least 6,000 students died in the residential schools. Most parents never knew that their child had perished. 11 The death toll of so many students from tuberculosis and other diseases in the residential schools has recently prompted a heated debate about Canada’s responsibility for these deaths.

- 1For example, he was responsible for “the outlawing of Aboriginal dance along with the spiritual and cultural ceremonies within which such dancing took place such as the Potlatch and the Sundance.” Nancy Chater, Technologies of Remembrance: Literary Criticism and Duncan Campbell Scott’s “Indian Poems” (master’s thesis, Toronto University, 1999), 25–26, accessed September 12, 2014.

- 2Nancy Chater, Technologies of Remembrance: Literary Criticism and Duncan Campbell Scott’s “Indian Poems” (master’s thesis, Toronto University, 1999), 26, accessed September 12, 2014.

- 3Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1986), 22.

- 4Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1986) 91–92.

- 5National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, vol. 6810, file 470-2-3, vol. 7, 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3).

- 6This phrase is incorrectly attributed to Scott, though he would likely have agreed with this idea. It belongs to the American Captain Richard H. Pratt. See Mark Abley, “The man wrongly attributed with uttering ‘kill the Indian in the child’,” Maclean’s, accessed September 12, 2014. See also “‘Kill the Indian, and Save the Man’: Capt. Richard H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans,” History Matters website, accessed September 12, 2014.

- genocidegenocide: In 1944, Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide to describe the intentional and systematic destruction of a racial, political, or cultural group. Genocide stems from the Greek word genos, which means “race,” and cide, which means “to destroy.” It was legally defined in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948 (the Genocide Convention). When the Canadian government selectively ratified the Genocide Convention in 1952, it excluded crucial elements of the convention. Many indigenous leaders, activists, and politicians have publicly called on the Canadian government to recognize the Indian Residential Schools system as genocide.

- 7James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision, 116; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children, 6.

- 8George Erasmus, “Notes on a History of the Indian Residential School System in Canada,” presented at “The Tragic Legacy of Residential Schools: Is Reconciliation Possible?” conference, hosted by the Assembly of First Nations/ University of Calgary, March 12–13, 2004.

- Indian Residential Schools systemIndian Residential Schools system: Beginning in 1883, the federal government sought a system to enroll indigenous children in schools. The residential schools system was part of a larger government agenda to assimilate indigenous people into settler society by way of education. Relying almost exclusively on churches to provide the teachers, administrators, and religious instructors, the system was severely underfunded and marked by inferior educational standards and achievement: neglect, malnutrition, abuse, and disease were widely reported. In recent years, researchers discovered that some schools even carried out dangerous medical experiments. It is also estimated that more than 6,000 students died of disease and abuse while enrolled. Over a 150-year span, the government and churches operated close to 150 schools where some 150,000 indigenous youth were enrolled.

- 9Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada, 93.

- 10Megan Sproule-Jones, “Crusading for the Forgotten: Dr. Peter Bryce, Public Health, and Prairie Native Residential Schools,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 13 (1996), 218–19.

- 11John Paul Tasker, “Residential schools findings point to ‘cultural genocide,’ commission chair,” CBCNews, May 29, 2015, accessed June 16, 2015. See also Brenda Elias, “The challenge of counting the missing when the missing were not counted,” paper presented at the International Association of Genocide Scholars conference, “Time, Movement, and Space: Genocide Studies and Indigenous Peoples,” July 16–19, 2014, University of Winnipeg.