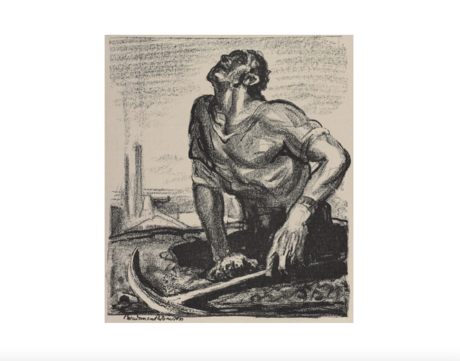

The Cost of Labour

Overview

About this Lesson

In the previous lesson, students explored the character of Mr Birling, analysing Priestley’s presentation of him and selecting relevant evidence to support claims about his character. Students also reflected on the connection between Mr Birling’s identity and his values, before considering their own identities and values. This critical engagement with the text and themselves laid the foundation for exploring the relationship between moral codes, values, and choices.

In this lesson, students will continue to examine the morals and values of the world which the characters inhabit, a world which Priestley meant to be representative of Edwardian society. Through this investigation, they will learn a new concept – universe of obligation – the term sociologist Helen Fein coined to describe the circle of individuals and groups within a society ‘toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for amends’. 1 Understanding the concept of a universe of obligation provides important insights into the behaviour of individuals, groups, and nations throughout history. It also helps students think more deeply about the benefits of being part of a society’s ‘in’ group and the consequences of being part of an ‘out’ group.

After having explored the concept of a universe of obligation, students will continue to read the play, before starting to consider the moral choices that the characters, notably Mr Birling, made in the past. They will then explore the theme of responsibility in the form of a debate, referring to Mr Birling’s sacking of Eva Smith for leading the strike action for higher wages. It is worth remembering that Mr Birling’s sacking of Eva Smith would have occurred during the period known as ‘The Great Labour Unrest’ (1910–14), when members of the working class took to the streets in mass actions and strikes, demanding fairer workers’ rights. The activities in this lesson will deepen students’ understanding of the characters in the play and the key theme of social responsibility, whilst encouraging them to reflect on society at large and think about what forces decide who is worthy of respect and caring, and who is not.

The activities in this lesson refer to pages 10–16 of the Heinemann edition of An Inspector Calls.

- 1Helen Fein, Accounting for Genocide (New York: Free Press, 1979), 4.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Part I Activities

Part II Activities

Extension Activity

Homework Suggestion

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

The Cost of Labour

Understanding Mr Birling

Persuasive Writing: A Letter to Parliament

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand