Exploring Identity (UK)

Overview

About This Lesson

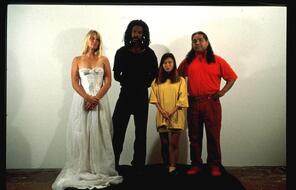

‘Who am I?’ is a question all of us ask at some time in our lives, and it is a particularly critical question for adolescent students’ own social, moral, and intellectual development. Our society – through its particular culture, customs, institutions, and more – provides us with language and labels we use to answer that question for ourselves and others. These labels are based on beliefs about race, ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation, economic class, and so on. Sometimes our beliefs about these categories are so strong that they prevent us from seeing the unique identities of others. Sometimes these beliefs also make us feel suspicion, fear, or hatred towards some members of our society. At other times, especially when we have an opportunity to get to know a person, we are able to see past labels and, perhaps, find common ground even as we appreciate each person as unique.

Through the analysis of a short story and the creation of their own visual representations of their identities, this lesson invites students to consider how the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ arises from the relationship between the individual and society (the first stage of Facing History & Ourselves’ scope and sequence) – the ways in which we define ourselves and the ways in which we are defined by others.

Understanding identity is not only valuable for students’ own social, moral, and intellectual development, it also serves as a foundation for examining the choices made by individuals and groups in the historical case study later in the unit. The factors that influence our identities are too numerous to capture in a single lesson. Chapter 1 of Holocaust and Human Behaviour includes resources that address a larger variety of factors that influence identity, most of which can easily be added or swapped into the activities of this lesson.

In some environments, it might be especially important to address one specific identity: Jewish identity. Because Jews were a primary target of malicious stereotyping, discrimination, and horrible violence in the historical period explored later in this unit, it is important for students to have a basic understanding of the faith, culture, diversity, and dignity inherent in Jewish identity. In some schools and communities, students may not know anyone who identifies as Jewish, or they might not have had any exposure to Jewish faith, culture, and diversity. It is important to help students recognise that identifying as Jewish implies membership in a rich and diverse set of beliefs and cultural practices.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before you teach this lesson, please review the following guidance to tailor this lesson to your students’ contexts.

Lesson Plan

Activities

Extension Activity

Materials and Downloads

Exploring Identity (UK)

Introducing the Unit (UK)

Single Stories (UK)

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand