Social Systems and Individual Agency

Overview

About this Lesson

In the previous lesson, students explored the character of Inspector Goole, discussing the message and modern relevance of his final speech on social responsibility. This process both assisted students in preparing for their GCSE exam and gave them the opportunity to consider the relevance of the play and the lessons we can learn from it.

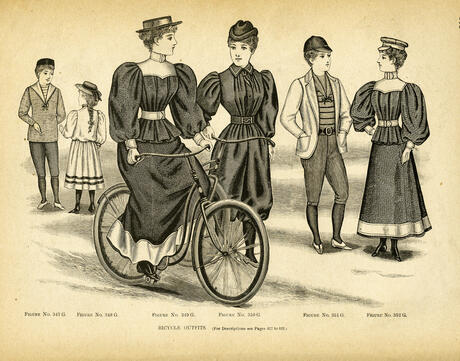

In this lesson, students will develop their understanding of human choices and behaviour by considering the social systems, such as class and patriarchy, that are operating in the play and in the society in which we live. These systems can influence our status in society and the amount of power we possess. The situation is complex, however, as there are multiple systems operating at the same time: one may give a person power in some areas, whilst another may render that same person powerless elsewhere. Since these systems can dictate how much power we possess and the scope of our influence – the Edwardian patriarchal system, for example, gave men greater rights than women, placing women in a subservient position – it is important to understand that they can have an impact on our experiences and, in some cases, may push people towards certain choices. However, it is also vital that students acknowledge that just because people operate within these social systems it does not mean they are not accountable for their actions. Ultimately, we are responsible for the choices we make, even if we feel ourselves pressured by the structures of a system.

Students will then move on to learn about the roles of perpetrator, victim, bystander, and upstander, and identify how these roles are relevant to understanding the characters’ decision-making processes. Working in groups, students will explore the behaviour of one character in the play by focusing on two events (one in relation to their treatment of Eva Smith, and the other in relation to their behaviour at the dinner party). When students share their ideas, they will be able to see how the characters change and adopt a range of roles. In some moments, for example, they may behave like perpetrators; in others, like upstanders; and elsewhere, they may adopt two roles simultaneously. Their position in society may make them victim to a social system with limited power, whilst the choices they make may place them firmly in the role of perpetrator. Encouraging students to explore these roles through the characters will enable them to consider their fluid nature – people can move between roles and can occupy different ones at the same time – and their highly complex nature. These roles do not exist alone, and we must also consider the context of the situation and the amount of power people possess. Such understanding is important if students are to reflect on their behaviour and realise that they play a part in the society in which they live: what they do or don’t do has consequences that reach beyond their own lives.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Part I Activities

Part II Activities

Extension Activity

Homework Suggestion

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

Social Systems and Individual Agency

Inspecting Inspector Goole

Putting the Characters on Trial

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand