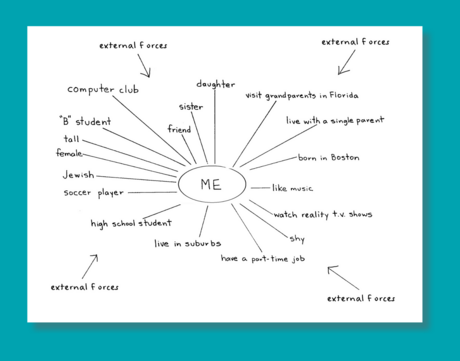

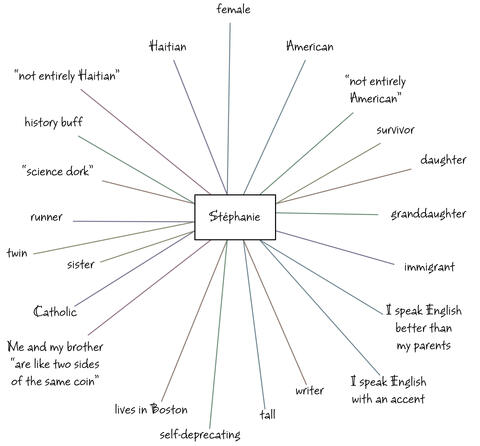

ELENA MAKER: Identity charts is infinite. There's so many things, and we're always adding things. And I like the flexible nature of the identity charts, and that it feels more organic, and it's inclusive of all parts of our identity. And so as we're talking, we can throw all these different things on the board. And then we can start to draw lines and connect them. And so I think for conceptualization and idea-generating, identity charts can be really helpful.

So we actually started in September. And it started off as an identity unit, which was inspired by "Facing History" and the identity readings that they have. Just to streamline the process was to make the "My Part of the Story" stories about the civil rights leaders. So we chose excerpts from-- each one of them had some sort of biography or autobiography. And we used those in class, and looked at these key words around labels, assumptions, voice, legacy, and identity, which are the key words in that identity unit.

Our essential question for the day-- Ernie, will you read it for us, please?

STUDENT 1: How do our personal stories influence how we choose to fight for justice?

ELENA MAKER: Excellent. So that is our essential question for the next three days. So we're beginning to put all this learning together to think about how different individuals' personal stories influence their fight for justice.

So the first thing we're going to do, and I know you all know how to do this, but we're going to make it a little more complicated today. So we're doing an identity chart. But in this identity chart, we are comparing and contrasting the experiences and beliefs of both Yuri and Angela.

So in your journal section-- so we're flipping to our journal section-- we're going to put Angela on one side of the page. And on the other, put Yuri. And leave plenty of space. So you want a whole journal page for this. So I'm going to challenge you. Before we talk about it together, I want you to think and write one thing about Angela's background.

All right. So what's one thing people wrote for Angela Davis, in terms of her experiences?

STUDENT 2: I said that when she was younger, she experienced a lot of bombings in her neighborhood.

ELENA MAKER: All right. Excellent.

STUDENT 3: Do we write that?

ELENA MAKER: Yep.

STUDENT 4: [INAUDIBLE]

ELENA MAKER: Great. So let's add to that. Where was her neighborhood?

STUDENTS: (IN UNISON) Alabama.

ELENA MAKER: Yes. Birmingham, Alabama.

All right. Arisela?

ARISELA: I said she grew into political activism when she was 12 or 11 years old.

ELENA MAKER: Yes. She was a young activist.

Carmen?

CARMEN: Wasn't her mom, like, an activist too?

ELENA MAKER: Yes, perfect. So we can add off of there.

So she said she doesn't even really remember when she started to become an activist, because she just grew up in this household where activism was part of their belief system. Yeah.

OK. Should we start with Yuri? Angie, and then Alex?

ANGIE: She grew up in a concentration camp.

STUDENT 5: Or internment.

ELENA MAKER: Internment camp. Did she grow up there?

STUDENTS: No.

(INTERPOSING VOICES)

She was 15.

ELENA MAKER: She went as a teenager, right? So intern--

All right. Olivia, you had your hand up?

STUDENT 6: She didn't start active-- like, she didn't become an activist until, like, she was 40.

STUDENT 7: Yeah.

ELENA MAKER: Anyone know-- remember why that was?

STUDENT 8: That's when she moved to Harlem?

ELENA MAKER: Yes. And why do you think Harlem made that change-- helped her make that change into an activist? What was going on in Harlem?

STUDENT 9: Was it because of the rules and stuff like that?

ELENA MAKER: She saw some inequality, right? She saw some segregation.

We do identity charts in their freshman year, and at the beginning of the year. They're very used to talking about issues around identity at Blackstone our social studies curriculum in general really focuses on that.

They have some vocabulary and some structure by the time they get to me sophomore year. And I also hope that in the Socratic seminar, as they're discussing, X person had this experience as a young person, and it led them to take this action, maybe they'll say something similar. And so I'm hoping that they're starting to make those connections in their own lives. And that's something we can discuss after this once I have the content down.