Le cahier de réflexion dans une classe FHAO

Overview

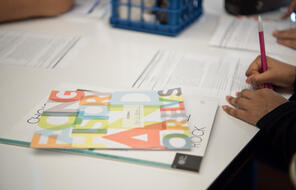

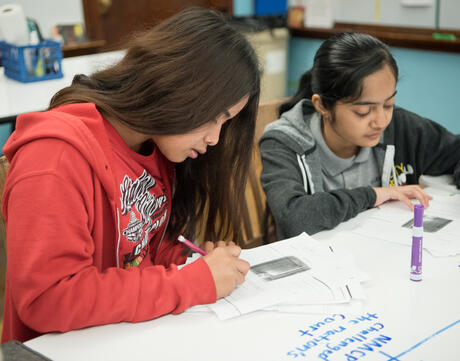

On peut appeler « cahier de réflexion » tout ce qui peut servir à noter et conserver ses pensées. Les feuilles volantes et les cahiers reliés forment tous deux d’excellents supports. Beaucoup d’élèves trouvent qu’écrire ou dessiner dans un cahier de réflexion les aide à assimiler des idées, à formuler des questions et à retenir des informations. Les cahiers de réflexion rendent l’apprentissage plus visible, car ils fournissent un espace accessible et sûr où les jeunes peuvent exprimer ce qu’ils pensent, ce qu’ils ressentent, ce dont ils doutent. Ils constituent aussi un outil d’évaluation, qui permet de mieux saisir ce que les élèves savent ou ce qu’ils ont du mal à comprendre et de juger de leur évolution au fil du temps. Mais les cahiers de réflexion ne servent pas uniquement à développer l’esprit critique, ils permettent aussi de créer une communauté d’apprenants. Chaque fois qu’’ils lisent ou commentent leurs écrits, les profs créent des liens avec les élèves. Et en écrivant fréquemment dans leur cahier de réflexion, ces derniers apprennent à s’exprimer avec plus d’aisance à l’écrit comme à l’oral.

Il y a bien des façons d’utiliser le cahier de réflexion. Certains noteront leurs idées pendant les cours et d’autres ne s’en serviront que pour un devoir particulier. Certains auront besoin d’instructions précises alors que d’autres s’exprimeront avec aisance, sans intervention extérieure. Tout comme il y a des différences entre les élèves, il y a des différences dans l’utilisation que les profs font du cahier de réflexion. C’est un outil pédagogique à usages multiples et l’on trouvera ci-dessous six suggestions fondées sur plus de trente ans d’expérience avec des enseignants comme avec des élèves.

Procedure

Questions à envisager lorsqu’on utilise le cahier de réflexion en classe

Journal Prompts for Middle and High School Students

These journal prompts reflect themes that many high school students and middle school students encounter as they come of age. Select from these prompts or use them as inspiration to write your own journal prompts.

Student Journaling Classroom Examples

Additional Resources

Resources from Other Organizations

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand