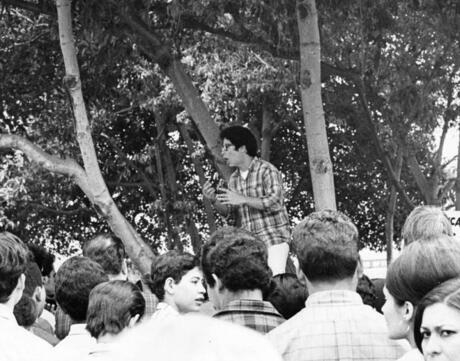

The 1968 East LA School Walkouts

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

9–12Duration

Two 50-min class periods- Racism

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

Overview

About This Lesson

In this lesson, students will learn about the relationship between education, identity, and activism through an exploration of the 1968 East Los Angeles school walkouts. Thousands of students in LA public schools (where a majority of students were Mexican American) walked out of their schools to protest unequal educational opportunities and to demand an education that valued their culture and identities. Learning about this history provides students with an opportunity to reflect on the importance of an education that honors the identities of its students.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before you teach this lesson, please review the following guidance to tailor this lesson to your students’ contexts and needs.

Lesson Plans

Day 1

Day 2

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

The 1968 East LA School Walkouts

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand