How do you find a voice when society censors you? How do you find a voice when, as a woman, you are not able to feel empowered by a very, very patriarchal society? How do you find a voice when you have been victimized? And yet they found a voice. And I think, if you ask me, what is the most important thing about arpilleras, it's the ability of people who have been victimized to tell their own story.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Chile is a country stretching narrowly along the western coast of South America. In 1970, a new movement came to power in Chile. The country elected President Salvador Allende, who inspired a whole generation with hopes for deep social and democratic reforms. But he was met with a harsh backlash and was overthrown in 1973 by General Augusto Pinochet.

Pinochet violently ended 130 years of imperfect but democratic tradition and replaced it with 17 years of military dictatorship. During the Pinochet reign, tens of thousands of people were abducted, interrogated, and tortured. Over 3,000 people vanished without a trace. Thus began the long and painful search of thousands of wives, sisters, and mothers for Chile's disappeared sons.

It was a time of silence, of fear, of empty streets, of curfews, of bombs in the middle of the night. But the fear was not-- at the beginning was visible. People were detained. Men that had long hair were immediately shaven in a public place. But the fear then transformed to something that I consider more danger, was the invisible fear.

Those that you trusted were no longer trustworthy. The books you always believe you could read and could give you some answers were forbidden. Doors were closed. Nothing was safe. And I think those are the horrors of dictatorship. The uncertainty is so profound that you lose this great concept that we had, which was to be a citizen with rights. I think we became a society of vigilantes, informers, instead of a society of good neighbors.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

The people that were targeted were activists from high schools, universities, factories-- mostly those that were supporters of Salvador Allende and who fought for the transformation of society. Then, of course, the mothers of these activists-- because of their relationship to their children, after their children disappeared-- were also targeted. The children were activists, but they were not terrorists. The majority of them never used arms. They were idealistic young people, and that truth that they were murdered without a trial and that they were murdered in a very clandestine way, that their bodies were tortured, that their bodies were thrown into the sea, gave them a tremendous voice.

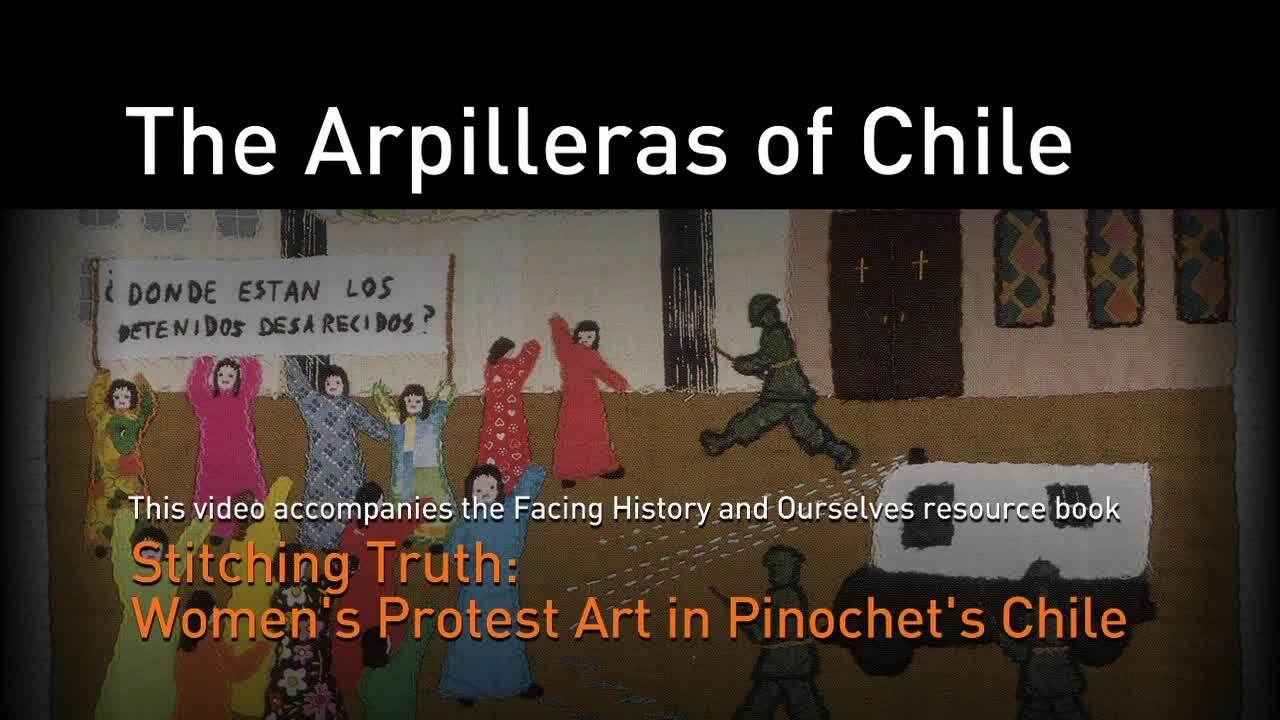

In 1974, one group of women, many of them mothers of disappeared people, came together to protest the brutal regime and demand the return of their loved ones. The focus of the protests were vivid, hand-stitched quilts that told the sad and gruesome stories of the disappeared. These quilts were called arpilleras, and the women who made them were known as arpilleristas.

I started hearing about the arpilleristas in 1976. I was a graduate student at Indiana University. So we had a visiting lecturer, a very important writer, Antonio Skármeta, who was escaping Santiago on his way to Berlin. He had, in his little portfolio suitcase, one single arpillera that he had folded. And he opened it to the classroom.

I was very young, coming from a very idealistic family, and I became so mesmerized by this because it touched my heart, it was poignant, it was portable, it told a story. And I, as a young graduate student, said, this is what I want to do. I want to study this. I want to learn more about it.

So I just went and knocked at the door of the main office of the Catholic Church. And in 1974, they had formed a very special committee called Pro-Peace Committee and Vicariate of Solidarity, which was to help the victims of the Pinochet terror. And Raúl Silva Henríquez, a very important human rights figure in the Church, set up this committee to protect victims. And I knew that the arpilleristas met there. These mothers, before they made the arpilleras, found themselves searching together in similar places like tribunals of justice, hospitals, and morgues. And they began to recognize each other and then collectively went to seek help to the Vicariate of Solidarity and to denounce the disappearances of their children.

If they knew that in a particular house in downtown Santiago called Londres 33, which happens to be a torture center, now a museum, were torturing people. They went home, made the initial stitching of the arpilleras, the arpillera that speaks about torture. Then they brought these arpilleras to the Vicariate of Solidarity. And then in the evening, they went into a street demonstration.

They worked together. They were empowered by the communal experience. They went to protest, to the streets in front of the torture centers, in front of hospitals. They used to chain themselves in front of the former tribunals of Congress. The central issue for them was the search for their missing children.

It was '77, '78. Around '79, '80, the missing children became a very central part of the arpillera itself, but the women realized that they will never find their children. And none of those women that I met, that I interviewed, that I became friends, ever found out where their children are.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So the search for a loved one was always linked to the search for beauty or to the search for making art or denouncing what has happened. It was-- their lives and their art was inseparable. And this is why, in the arpillera itself, they may use clothing of the deceased, a piece of hair that they had saved from the child. Uniforms in Chile are very light blue like the sky. In order to create the sky, they used their children's shirts. And it's an art that doesn't have divisions between the life of an artist and the life of an ordinary citizen. It all merges into one with incredible force.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

They found a voice through art. And they found their voice, is something I think a lot, through the power of the human hand. We live in such a global world where everything is manufactured through machinery. But the human hand, the construction of the story, stitching piece by piece, a life-- but not an ordinary life, but a life that has been cut off.

I learned from them about empathy, compassion, commitment. But I also learned something that I think is so lacking in our society, which is to put oneself in somebody else's shoes, to deeply engage with the life of another human being. And not only a human being that suffers, but your own neighbor, your own son, daughter, wife-- the whole fabric of society.

It's a very complex question-- what gives people strength? What gives people the power to say, enough? What gave them the strength was truth. That simple and that complex.

[MUSIC PLAYING]