Changing Names

At a Glance

Subject

- History

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

- Human & Civil Rights

- Racism

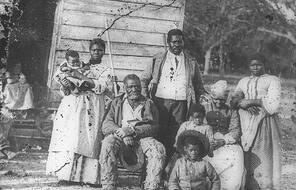

After Emancipation, many former slaves adopted new names and surnames. They did so either to take on a surname for the first time, or to replace a name or surname given to them by a former master. Here, three different former slaves discuss their names and the changes they underwent after Emancipation.

In the 1930s, ex-slave Martin Jackson explained why he chose his last name after Emancipation:

The master's name was usually adopted by a slave after he was set free. This was done more because it was the logical thing to do and the easiest way to be identified than it was through affection for the master. Also, the government seemed to be in a almighty hurry to have us get names. We had to register as someone, so we could be citizens. Well, I got to thinking about all us slaves that was going to take the name Fitzpatrick. I made up my mind I'd find me a different one. One of my grandfathers in Africa was called Jeaceo, and so I decided to be Jackson. 1

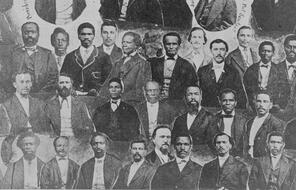

Dick Lewis Barnett and Phillip Fry were African American veterans of the Union Army during the Civil War. In 1911, Barnett and Fry’s widow, Mollie, both applied for pensions from the government. This financial assistance was available to all Civil War veterans and their families. However, many African Americans faced a problem when they applied for their pensions. After the war ended and slavery was abolished, they exercised their freedom by changing their names. This meant that army records documented their service with their old names instead of their new ones. In order to receive their pensions decades later, these former soldiers and their family members had to demonstrate to the government that they were who they claimed to be. The following documents are excerpts from government records in which Dick Barnett and Mollie (Smith) Russell explain when and why they changed their names.

Testimony of Dick Lewis Barnett, May 17, 1911:

I am 65 years of age; my post office address is Okmulgee Okla. I am a farmer. My full name is Dick Lewis Barnett. I am the applicant for pension on account of having served in Co. B. 77th U.S. Col Inf and Co. D. U.S. Col H Art under the name Lewis Smith which was the name I wore before the days of slavery were over. I am the identical person who served in the said companies under the name of Lewis Smith. I am the identical person who was named called and known as Dick Lewis Smith before the Civil War and during the Civil War and until I returned home after my military service . . .

I was born in Montgomery County, Ala. the child of Phillis Houston, slave of Sol Smith. When I was born my mother was known as Phillis Smith and I took the name of Smith too. I was called mostly Lewis Smith till after the war, although I was named Dick Lewis Smith—Dick was the brother of John Barnett whom I learned was my father . . .When I got home after the war, I was wearing the name of Lewis Smith, but I found that the negroes after freedom, were taking the names of their father like the white folks. So I asked my mother and she told me my father John Barnett, a white man, and I took up the name of Barnett . . . 2

Testimony of Mollie Russell (widow of Phillip Fry), September 19, 1911:

Q. Tell me the name you were called before you met Phillip Fry?

A. Lottie Smith was my name and what they called me before I met Phillip and was married to him.

Q. Who called you by that name and where was it done?

A. I was first called by that name in the family of Col. Morrow in whose service I was in Louisville, Ky., just after the war. I worked for him as nurse for his children, and my full and correct name was OCTAVIA, but the family could not "catch on" to that long name and called me "LOTTIE" for short. LOTTIE had been the name of the nurse before me and so they just continued that same name. I was called by that name all the time I was with the Morrows. . . .

Q. Besides the Morrows, whom else did you live with in Louisville?

A. Mr. Thomas Jefferson of Louisville, bought me when I was three years of age from Mr. Dearing. I belonged to him until emancipation. They called me "OCK". They cut it off from OCTAVIA. It was after emancipation on that I went back to work for Col. Morrow and where I got the name "Lottie," as already explained. I liked the name better than Octavia, and so I took it with me to Danville, and was never called anything else there than that name. . . .

Q. How did you ever come by the name of "Mollie"?

A. After I had returned to Louisville from Danville, My sister, Lizzie White, got to calling me Mollie, and it was with her that the name started.

Q. Where did you get the maiden name of Smith from?

A. My mother's name was Octavia Smith and it was from her that I got it but where the name came from to her I never knew. I was only three years old when she died. No, I don't know to whom she belonged before she was brought from Virginia to Kentucky. 3

- 1Norman R. Yetman, ed., Voices from Slavery: 100 Authentic Slave Narratives (Dover Publications, 2012), 175.

- 2Civil War Pension File of Lewis Smith (alias Dick Lewis Barnett), Co. B, 77th US Colored Infantry, and Co. D, 10th US Colored Heavy Artillery, Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- 3Civil War Pension File of Phillip Russell (alias Fry), 114th US Colored Infantry, Record Group 15, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Get the Reading

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Changing Names," last updated March 14, 2016.

This reading contains quoted text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.