Defining Universal Human Rights

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

Grade

11–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Human & Civil Rights

Overview

About This Lesson

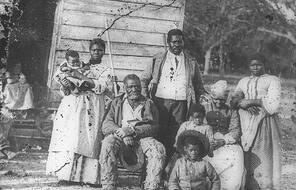

In this lesson, students will consider what rights should belong to every human being on earth, as well as the challenges of trying to create an international framework of rights for all. Students will first define a right and then reflect in their journals about the rights that they have, as well as rights that they don’t have but should, at home, at school, and in their communities. Then students will compare their definitions with UNESCO’s definition of a right and work with a group to reach a consensus about three human rights that they believe every person is entitled to enjoy.

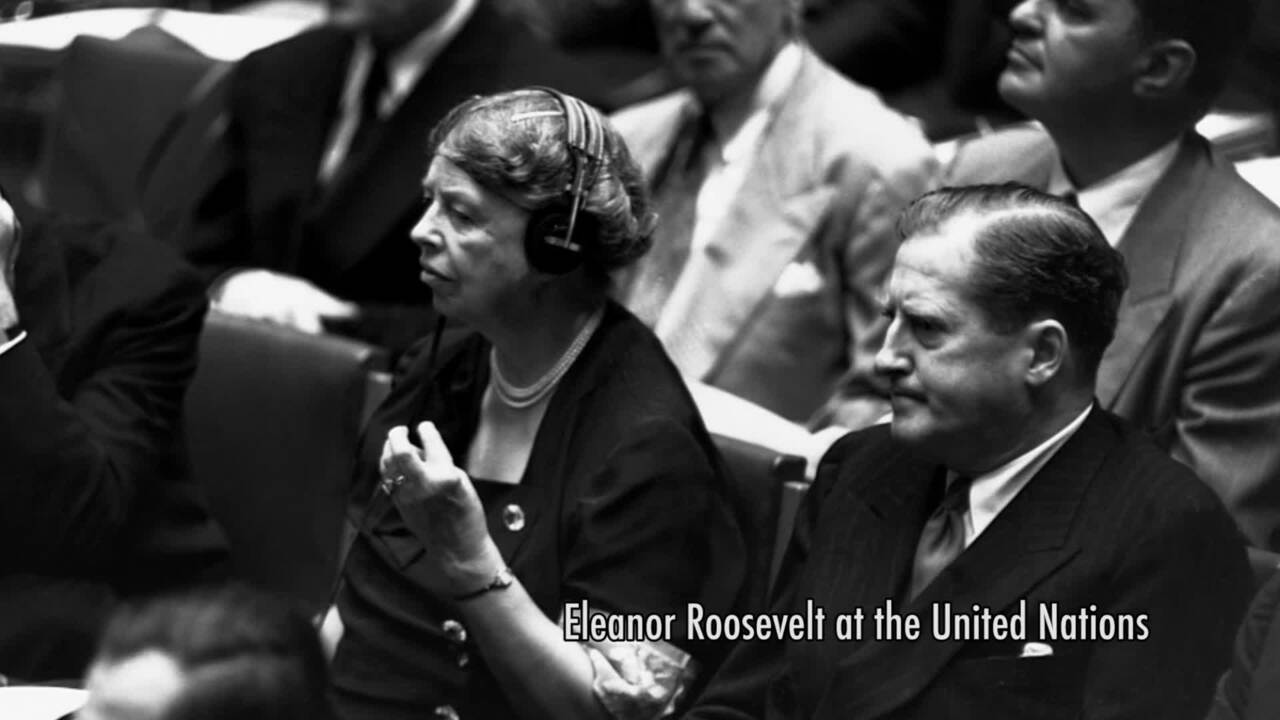

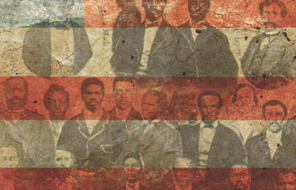

Finally, students will learn how the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, led by Eleanor Roosevelt, grappled with these same questions as UN representatives worked together to draft a Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the aftermath of the Great Depression, World War II, and the Holocaust.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Extension Activity

Materials and Downloads

Defining Universal Human Rights

Universe of Obligation and Human Rights

Complicating the Universality of Human Rights

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand