[MUSIC PLAYING]

The night of February 27, 1933, the German Reichstag, which is the symbol of parliamentary democratic process for Germany, explodes in flame from an arson attack. And was traumatizing. No one knew actually what had happened.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

But the Nazis exploited this to implement emergency decrees that suspended all the basic civil rights.

After the burning of the Reichstag, the threats from the right and the left, no one knew what was going to happen next, and there was a willingness for the average German to sacrifice civil liberties for the sake of national security.

And the Nazis use this as an opportunity to start rounding up the political opposition. In Bavaria alone, they round up 10,000 people. Now suddenly the prisons are over capacity. The jails are filled. They're using schools. They're using sports halls to contain these people.

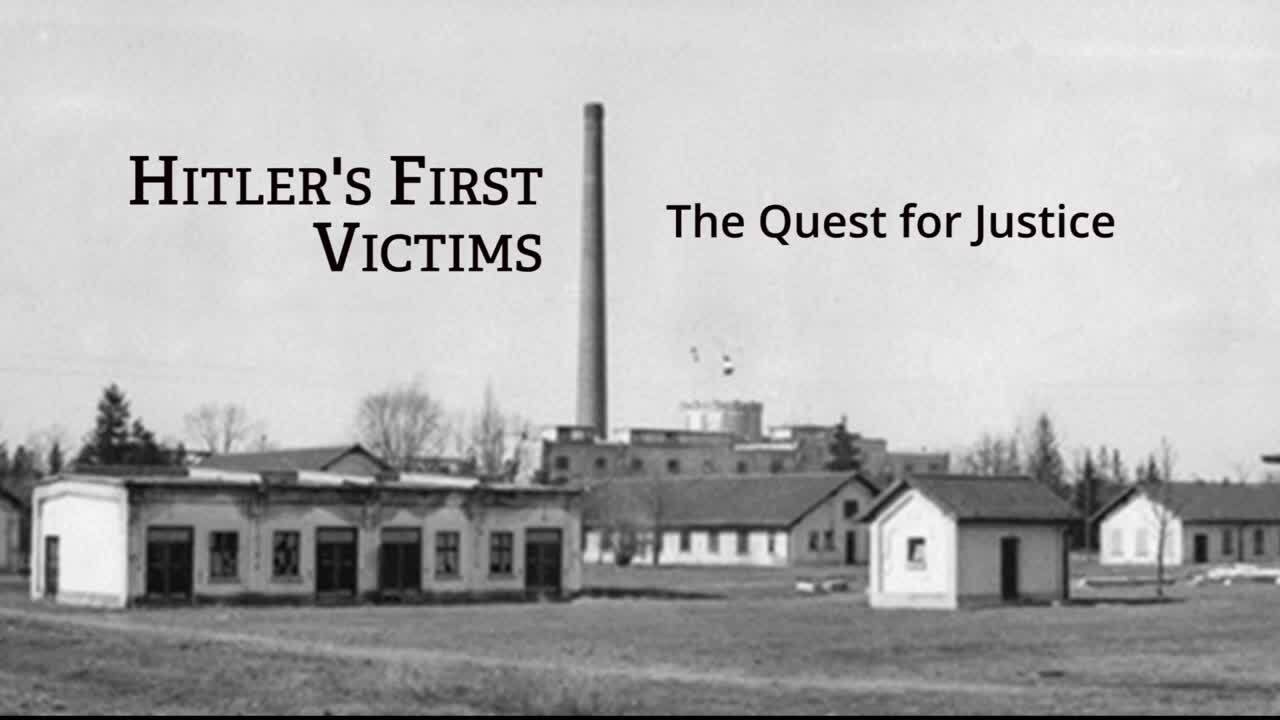

And you start getting from government officials, this is overburdening the system, so they find this abandoned munitions plant in late March, outside of the town of Dachau, and they start concentrating them in this facility.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

What's interesting about it is how haphazard the whole thing is. This is not this massive facility with thousands of people. Most interesting is that there was actually no legal parameters for this. The Nazis had simply started collecting people in there.

It was initially under state police protection. The guards were there. Suddenly they find all of these people there who have not been-- they have not been charged with any crime.

Well, the police officially protested to the state government, saying that the state police are being used for an activity which is illegal, because we're detaining people without arrest warrants, without any charges. This is where Himmler plays a very interesting role.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

He was the chief of the political police, but he was also head of the Nazi SS, which was the private security forces of the SS. What Himmler did was to put on his police cap and say, OK, I'm removing the state police from this facility. He then took off that hat and he put on his SS cap and he moved the SS in.

The state police leave on Tuesday, April 11. The SS come in, 120 of them. And so, suddenly, you have these individuals who are completely outside of any legal process.

The next day, shortly after 5 o'clock in the afternoon, within just over 24 hours, four detainees are shot in an alleged escape attempt. And this is where the Hartinger story begins.

In April 1933, Josef Hartinger was a deputy prosecutor for the large Bavarian jurisdiction called Munich II, a massive area of countryside around the city of Munich.

The phone rings on Thursday morning, April 13, saying that four detainees have been shot trying to escape. He is required by law to investigate any death by an unnatural cause.

So he calls Dr. Flamm, who is his forensic doctor. They get in a car and they drive 20 minutes north to the town of Dachau. They arrive there, and Hartinger is kind of surprised that there aren't any police around, but there are these SS.

He's led into an isolated area just outside of the camp. The bodies have been removed, which is in violation of procedure. The blood is still moist on the ground. He then asked to see the bodies.

And he's taken to a munitions shed that's even farther into the woods. And he finds these young men just thrown on this bare concrete floor. Dr. Flamm does forensic examination of the bodies. They're riddled with bullets. But what's most important is there's a single bullet in the back of each head.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

On the drive back, he's very troubled by this, and he says, you know, this is the day before Good Friday and Easter weekend, a very important holiday. So important in Bavaria that even the Nazis have agreed to offer an amnesty so that the detainees can go home for the Easter weekend. That's how important it is.

So Hartinger says, why is it that four men would try to escape right before this weekend Easter amnesty? Most consequentially for him, the fact that all four of these men were Jewish. He seemed to be the only one who noticed this.

But the next morning, he goes into the chief prosecutor's office, and he says, I think the Nazis are killing Jews in Dachau. His boss, who's a conservative but definitely not pro-Nazi, says, I know the Nazis and not even they would do something like that.

Adding to the surprising nature of the situation as a whole, the next week a reporter came from The New York Times to cover the story, writing an article that would fail to mention both the names of the murdered men, or that they were Jews.

The guy missed the story. But it fits with this idea that what we see as inevitable at that time was simply unimaginable.

Hartinger then-- over the next six weeks, there's a series of killings, and Hartinger just doesn't let go. Every time there's another killing reported, he shows up at the gate with Dr. Flamm. They collect this forensic evidence and gradually build a case.

And Hartinger is there. He's calling the Nazis at every single step. And he knew-- he understood the risks that he faced at that point.

Sadly, after carefully gathering evidence against the Nazis' abuses and cover-ups at the Dachau concentration camp, when Hartinger presented indictments against the camp commandant and other soldiers, his boss, the chief prosecutor, refused to sign them, fearing a Nazi reprisal.

Hartinger at that point could have said, I've done everything I was supposed to do. I've done my job. I guess there's nothing we can do. Hartinger goes back to his office and writes the indictments himself into the night and signs them personally. That night, when he goes home, he says to his wife, I've just signed my own death sentence.

The next day, Hartinger submitted the indictments. Unbeknownst to him, however, Heinrich Himmler, then head of the SS, had put himself in charge of all legal matters and administration relating to the camp. And so the indictments went directly to his office.

Hartinger is completely exposed and he expected the worst. But something astonishing happened. The Nazis had been killing people on a regular basis since those first four victims in April. On June 1, the killings stopped. So that by the end of July, killings in Dachau had ceased, and Hartinger actually assumed he was victorious.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

What he had actually done was to take-- just to throw a legal wrench into this killing machinery in Dachau. Hans Frank writes, saying, I am the Minister of Justice for Bavaria. I am ultimately going to be held accountable for these. I refuse to have the responsibility for what's going on in that camp.

And he basically pushed it away from himself. And what finally happened is these indictments were literally just locked in a desk drawer of the Gauleiter for Bavaria, and sat in his desk for the next 12 years.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

In the spring of 1945, an American officer is going through these Nazi headquarters. They break open this desk and they find his indictment files, and they become key evidence in the prosecution of the Nazis at the Nuremberg trials.

[MUSIC PLAYING]