Identity and Names

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Social Studies

Grade

7–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Democracy & Civic Engagement

Overview

About this Lesson

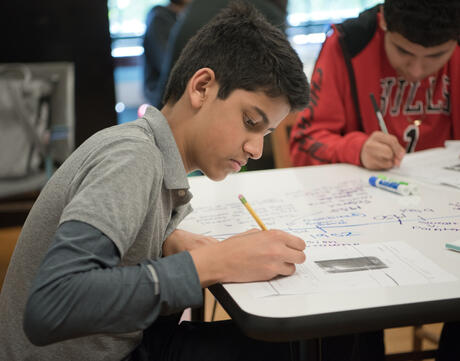

If each individual in the United States contributes to the nation’s collective identity, then it makes sense to start a course exploring United States history by thinking about the individuals who comprise the nation.

According to American author Ralph Ellison, “It is through our names that we first place ourselves in the world. Our names, being the gift of others, must be made our own.” 1 Indeed, when we meet someone new, our name is usually the first piece of information about ourselves that we share. It is often one of the first markers of our identity that others learn. In this lesson, we use names to introduce the concept of identity and the idea that each of our identities is the product of the relationship between the individual and society.

Students will then broaden their exploration of identity and consider the other factors that influence who we are as individuals. They will consider the parts of our identity that are given to us as well as the parts that we choose.

- 1Ralph Ellison, “Hidden Name and Complex Fate: A Writer's Experience in the United States,” in The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison, ed. John F. Callahan (New York: Modern Library, 2003), 192.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

Identity and Names

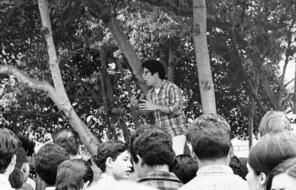

Finding Your Voice

Identity and Labels

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand