[MUSIC PLAYING]

One of the questions that we are frequently asked, and I think it's a challenging question, is, are you claiming that the Holocaust unfolded in North Africa? And Aomar and I have had many conversations about this with each other and with colleagues who disagree with us and who sometimes agree with us, and our conclusion is that one has to be incredibly careful and specific with vocabulary, historical terminology, and with how we understand and situate historical subjects.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

There were North Africans, absolutely, who were victims of the Holocaust, who were survivors of the Holocaust, who were partisans, who were resisters, who were deported to death camps, who survived death camps, who wrote memoirs, who passed through internment camps on their way to death camps, whose peregrinations through the war precisely mimicked those of European Jews.

Some of these were immigrants. Some of these were children of immigrants to Europe. Some of them were folks who were traveling as students or as professional athletes or as representatives or many other things. I would not employ the language of Holocaust survivors for the bulk of the population in North Africa. There was not a systematic policy of deporting Jews from North Africa or Muslims from North Africa to the camps, except for the Italian case, where the fascist regime deported Jews to concentration camps in Italy, and some of them did end up in the Nazi death camps.

But I would say this, and I think it's very important. We cannot tell a complete story of the Holocaust without understanding the pivotal role of North Africa and the way in which the entire machine of Nazism and Italian fascism percolated through North Africa in very complex ways.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We have to understand how Italian occupation of Libya was a testing ground for the unfolding of race laws that Nazi Germany would implement and expand upon later. So in many, many ways, while I think one has to be careful to draw a distinction between Holocaust history and wartime North African history, we fail as historians of the Holocaust if we separate these stories.

And we have to be expansive in our understanding, while not giving up on any of our historical rigor of identifying who experienced what and when and how.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

The fascist occupation of North Africa unfolds in stages. It begins with fascist Italian occupation of Libya in 1911 and then will only slowly be enforced upon regions under French control and finally in Tunisia, which the Nazis occupied directly.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

It is in the spring of 1940 when Germany occupies France and a collaborationist regime is established in France in the southern city of Vichy. Northern France is directly occupied by the Nazis. The southern part of France as well as all areas that were under French colonial control now fall under the rule of the Vichy regime.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

And in the months that follow, just as the Vichy regime will impose race laws mimicking those of Germany upon the peoples living in Vichy, France, so, too, will it impose race laws upon its subjects in the colonial world.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

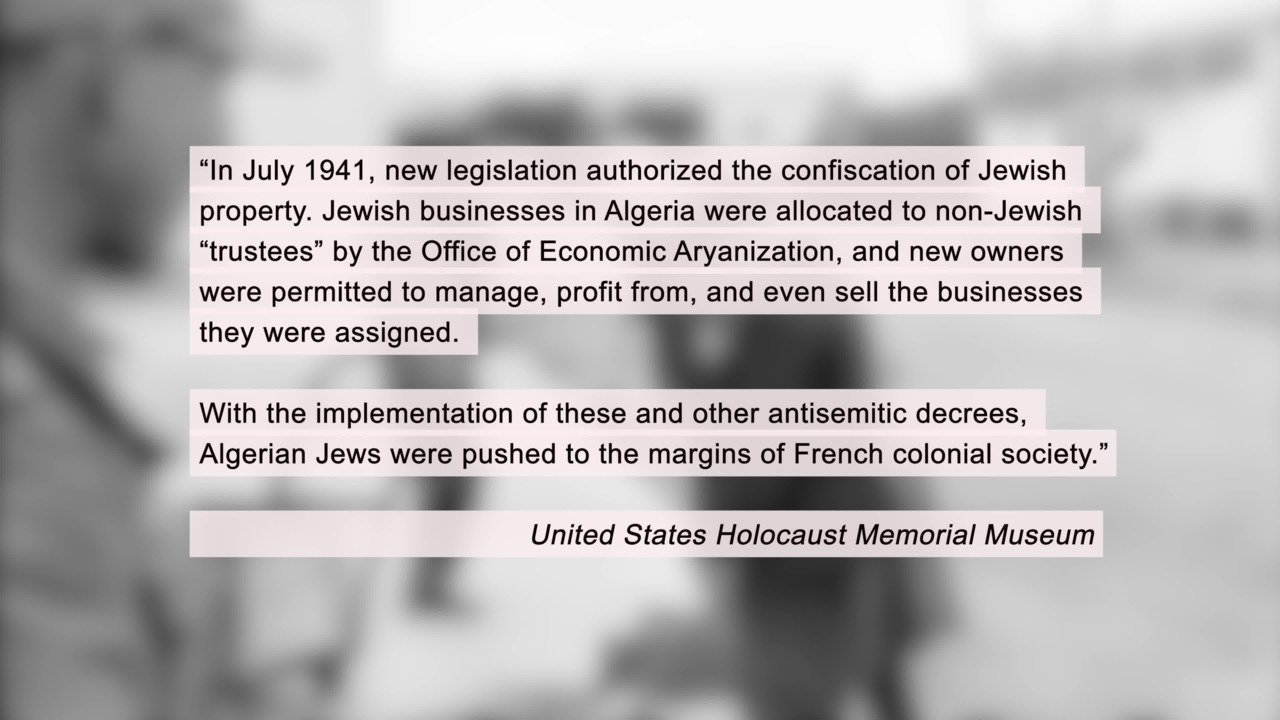

And those laws will not only try to legally construct Jews through these antisemitic laws, but also you start seeing what you call the Aryanization of these societies.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

And it will create divisions between a Jewish population and a non-Jewish population. In time, the Vichy regime will also create ribbons of camps running across North Africa. There are prison camps. There are detention camps. There are labor camps.

And there will be sent to these camps an immensely diverse range of people, including Muslim, anti-colonial nationalists, including European Jewish and Christian refugees who fled Europe with the rise of Nazism or, and here it gets very intricate, who fled to France to volunteer for the French Foreign Legion-- mostly Jews, but some Christians as well.

And after France falls to Germany, they are deported to the North African camps. And they will find themselves sharing a terrifying and uncertain life in these camps, often being moved, which was a strategic goal of the Vichy regime to move people as a force of disorientation. They will work under conditions of forced labor. They will experience exposure to the elements, malnutrition, poor hygiene. Families will be separated.

So I think what's interesting is this movement of people from northern part of the Mediterranean, from Marseilles and other camps in Europe to North Africa, to serve this structure of economic colonial structures, Vichy colonial structures. So really one of the most interesting phenomenons you have in North Africa.

It resembles in some ways certain structures of labor in mainland Europe that the Germans tried, but it's different. And if you want to compare and contrast, that's where you start seeing some of these interesting ways to think about how people were moved around, how people were also used to extract more the resources of the land. Because these camps were also tied to mines.

And many of these mines in the Sahara, the idea of moving these natural resources to the sea to the Mediterranean to be sent to Europe, so that's also linked to a bigger colonial German structures. So one of the camps of Bou Azzer, for instance, a cobalt mine, the Germans had their eyes on that going back to 1911.

I want to mention something else that we haven't had the opportunity to speak about yet, and that is the way in which the history of Black West Africans intersects with the histories that we're already telling here.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

France, before World War I, conscripted all these West Africans and Central African soldiers to implement its colonial policy in Morocco that used them in World War I to fight the Germans. And then you have to wait till World War II for the Germans to construct their ideology of race that a lot of German anthropologists have played a role in, as early as the 1920s, that Hitler was also influenced by as far as race, is also later on be implemented in-- that will affect the way German soldiers, Nazis soldiers-- when they occupied France, one of the first things they did, they killed all these Black soldiers.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

During the Second World War, conscripts from West Africa, Indigenous Black Moroccans, are forced to serve as overseers in the camps, especially in the Sahara. These so-called representatives of French authority are really more than prisoners themselves.

And generally speaking, what is so astonishing is that we have a whole other population whose history is rooted in the history of colonialism, whose oversight by France is entirely shaped by colonial realities, by racism, and specifically by anti-Blackness, and that their history comes to intersect directly in a very, very interpersonal, face-to-face fashion with all of the other myriad people who come to reside in these camps.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

And so it offers us a really vivid example of how anti antisemitism, Islamophobia, and anti-Blackness came together in North Africa through the complicated web of colonialism intersecting with fascist rule.

And so what's crucial about it is this idea that, generally, West Africa is left out of this story of not only French colonial presence, but also the period of the Holocaust.

[MUSIC PLAYING]