Negotiating the Convention on the Punishment and Prevention of the Crime of Genocide

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Genocide

Humanitarian intervention—military action that is intended to protect victims of war crimes and genocides—was not new. In 1827 England, France, and Russia intervened to put a stop to atrocities committed during the Greek War of Independence. In 1840 the United States intervened on behalf of the Jews of Damascus and Rhodes; and the French attempted to stop religious persecution in Lebanon in 1861. Several efforts were also made to stop pogroms against the Jews and other minorities in Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

These attempts were carried out in the name of the international community. According to Leo Kuper’s pioneering study of genocide, they showed that banning such crimes “had long been considered part of the law of nations.” 1 Moreover, in 1915, when the massacre of thousands of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire was reported, France, Great Britain, and Russia declared that such acts constituted “crimes against humanity and civilization”—a definition that later played a crucial role in the Nuremberg trials (see Reading 4: “Lemkin and the Nuremberg Trials” in Totally Unofficial: Raphael Lemkin and the Genocide Convention) and beyond. Yet Lemkin’s vision went far beyond these earlier examples of international action. He argued that unless a permanent method of humanitarian intervention and of prosecuting genocidal criminals was established, all responses to genocide would be limited and unsatisfactory.

After the Nuremberg trials began, Lemkin traveled constantly from one international conference to another. He “buttonholed delegate after delegate. Always the answers were evasive. Genocide was an evil but what can be done about it?” 2 Exhausted and discouraged, Lemkin fell ill in Paris and checked himself into the American Military Hospital. As he lay in bed reading, a news item caught his attention: the United Nations, which had been created in 1945 to replace the League of Nations, was about to hold its inaugural meeting in Lake Success, New York (home of the United Nations in its first years). 3 Lemkin immediately left the hospital and rushed to catch a plane.

On arriving at Lake Success, Lemkin talked to every delegation that would listen, asking them to “enter into an international treaty which would formulate genocide as an international crime, providing for its prevention and punishment in time of peace and war.” 4 During these months, Lemkin proved himself a relentless activist. While he was the main lobbyist for a United Nations’ treaty to outlaw and prevent genocide, he did not act alone. He contacted many leading journalists and enlisted them to promote this idea. Prodding them with kind words and moral principles, he spread the word about his new idea. Lemkin also turned to other lobbyists for help.

A number of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)—organizations that are not funded by the state but by individuals who want to promote different causes—supported Lemkin’s cause and helped him put pressure on United Nations delegates to promote it. Among these NGOs were the National Conference of Christians and Jews (one of the oldest human rights organizations in the United States, which recently changed its name to the National Conference for Community and Justice) and B’nai B’rith, a Jewish mass membership organization. 5 Tirelessly, he wrote innumerable pamphlets, petitions, newspaper articles, and personal letters to advance his idea. Lemkin was therefore a lobbyist, a strategist, and an agitator, all in one person.

Soon it became clear that two categories of nations were most likely to accept his ideas: those that were small and those whose continuing conflicts with powerful, aggressive neighbors made them want the protection a genocide law would offer. The first countries to endorse his proposal were Panama, India, and Cuba.

Next, Lemkin approached each delegation separately, explaining the details of what each nation had to gain from a discussion of genocide. He sent innumerable letters, sometimes pleading, sometimes flattering or scolding the delegates. Finally, on December 11, 1946, the General Assembly of the United Nations unanimously resolved that genocide was “an international crime and that a treaty should be drawn up” to punish those who carried it out. 6 Genocide would be defined as “a denial of the right of existence of entire human groups, as homicide is the denial of the right to live of individual human beings; such denial of the right of existence shocks the conscience of mankind, results in great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions represented by these groups, and is contrary to the moral law and to the spirit and aims of the United Nations.” 7

Nearly two years of work by United Nations committees went by before the General Assembly met on December 9, 1948, in Paris to vote on the treaty that would become the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the Genocide Convention). One of Lemkin’s biographers described the scene:

The professor waited tensely in the Palais de Chaillot. For many years he had been working for this moment. After countless failures, the nations of the world were now ready to act on his plan. He listened intently as the roll was called, his heart beating faster and faster as he heard the delegates of nation after nation vote “Yes.” Finally there were fifty-five votes in favor of the treaty. 8

A storm of applause erupted in the hall. Hundreds of flashbulbs exploded in Lemkin’s face. “The world was smiling and approving,” Lemkin wrote, “and I had only one word in answer to all of that, ‘Thanks.’” 9 And then, Lemkin wrote, all was calm.

The Assembly was over. Delegates shook hands hastily with one another and disappeared into the winter mists of Paris. The same night I went to bed with [a] fever. I was ill and bewildered. The following day I was in the hospital in Paris. . . . Nobody had established my diagnosis. I defined it. . .as Genociditis: exhaustion from the work on the Genocide Convention. 10

A day later, on December 10, 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in another session of the General Assembly. The Genocide Convention and the declaration set new, universal standards for the treatment of individuals and groups in times of peace and war. While Lemkin had a number of reservations regarding the declaration, the two resolutions represented a rare moment of international unity and a focus on human rights.

✳ ✳ ✳

The convention declared that “genocide is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world.” 11 Lemkin had always believed that genocide should not be defined only as a war crime: in fact, the convention stated explicitly that it could occur “in time of peace or in time of war.” 12 The treaty also reflected two of his other obsessions: first, the crime would be extraditable—that is, those who committed such crimes could not seek asylum or refuge in other countries; second, the definition of genocide would go beyond mass murder to include the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part,” members of a specific group. Article II decreed that included in the definition are all “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” 13 The decision not to include any mention of what he called “cultural genocide,” the systematic destruction of a community’s heritage, was, by comparison, a minor disappointment for him.

Article II of the treaty, which defined the kinds of groups that had to be protected by international law, had caused a good deal of discussion. Many members felt that political groups, as well as national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups, needed legal protections. No doubt this was true, especially at a time when the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Stalin, was conducting a political witch hunt that left millions dead or imprisoned. But the Soviet Union was not the only member nation to object to including political groups in the treaty:

- Several nations argued that the protection of political groups was a human rights issue that should be dealt with by the United Nations Human Rights Commission.

- Others (including Venezuela, Iran, and Egypt) argued that political groups were changeable and difficult to define; in addition, they could not easily be distinguished from groups of workers, artists, or scientists, which did not need international protection.

- Many countries in which civil unrest was going on threatened to pull out of the treaty if their governments could not oppose subversive political groups without risking accusations of genocide. 14

Lemkin knew how damaging this debate could be to his cause. He used the term “political homicide” rather than “political genocide,” and he argued against including any references to political groups. If he had not been able to persuade the opponents of the Soviet Union on this point, the Genocide Convention would certainly never have been approved.

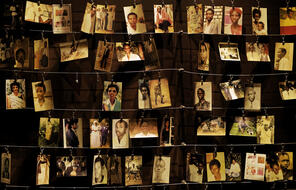

Every nation that signed the convention would be obliged to try genocidal criminals either at home or in international tribunals. Article VIII called upon them to “take such action . . . as they consider appropriate for the prevention and the suppression of acts of genocide.” 15 Although never legally used, Article VIII gave legal authority to the United Nations to fight crimes of genocide wherever they occurred. Article IX decreed that the International Court of Justice will allocate guilt and responsibilities of those who commit crimes of genocide. In the 1990s the clause was used to establish the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda—countries that experienced recent acts of genocide.

Officials who stood trial in these courts were often accused of genocide. In 1998 the permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) was established. The ICC’s jurisdiction is over a list of the most important international crimes. Genocide is the first crime on that list. 16

- 1Leo Kuper, Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth Century (New York: Yale University Press, 1981), 19.

- 2Robert Merrill Bartlett, They Stand Invincible: Men Who Are Reshaping Our World (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1959), 103.

- 3Information about the creation of the United Nations can be found in Dan Plesch, “The Hidden History of the United Nations,” Open Democracy website, http://www.opendemocracy.net/debates/article.jsp?id=6&debateId=134&articleId=2519 (accessed December 31, 2005).

- 4Raphael Lemkin, “Genocide,” American Scholar 15 (April 1946), 230.

- 5William Korey, An Epitaph for Raphael Lemkin (New York: The Jacob Blaustein Institute for the Advancement of Human Rights, 2001), 61-9.

- 6 Bartlett, They Stand Invincible, 104.

- 7Lawrence J. LeBlanc, The United States and the Genocide Convention (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), 23. The document quoted by LeBlanc is “General Assembly of the United Nations, Resolution 96 (I), December 11, 1946,” United Nations website, http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/033/47/IMG/NR003347.pdf?OpenElement (accessed November 3, 2005).

- 8Bartlett, They Stand Invincible, 105.

- 9Raphael Lemkin, Totally Unofficial Man: The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin, in Pioneers of Genocide Studies, ed. Steven L. Jacobs and Samuel Totten (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 2002), 394.

- 10Ibid., 395.

- 11LeBlanc, Genocide Convention, 245-46. The document quoted by LeBlanc is the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: General Assembly of the United Nations, Resolution 260A (III), December 9, 1948.

- 12 Ibid., 245.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14Ibid., 61-3.

- 15Ibid.

- 16Establishment of the International Criminal Court,” United Nations website, http://www.un.org/law/icc/general/overview.htm (accessed on October 4, 2005).

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Negotiating the Convention on the Punishment and Prevention of the Crime of Genocide," last updated March 16, 2008, https://www.facinghistory.org/.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.