The Power of Images

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Civics & Citizenship

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

9–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Democracy & Civic Engagement

- Racism

Overview

About This Lesson

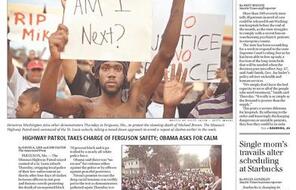

Sometimes a single photograph can have a far greater emotional impact than words alone could. This emotional potential makes photography a prime candidate for interpretation based on confirmation bias.

As illustration, this lesson includes an interview with St. Louis Post-Dispatch photojournalist David Carson in which he describes a photograph that was interpreted entirely differently by two groups of people. In a separate activity, students step into the role of news editor to choose the lead image that will run on the front page, based on a different scenario faced by the Post-Dispatch.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Get Files Via Google

The Power of Images

Social Media and Ferguson

#IfTheyGunnedMeDown

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand