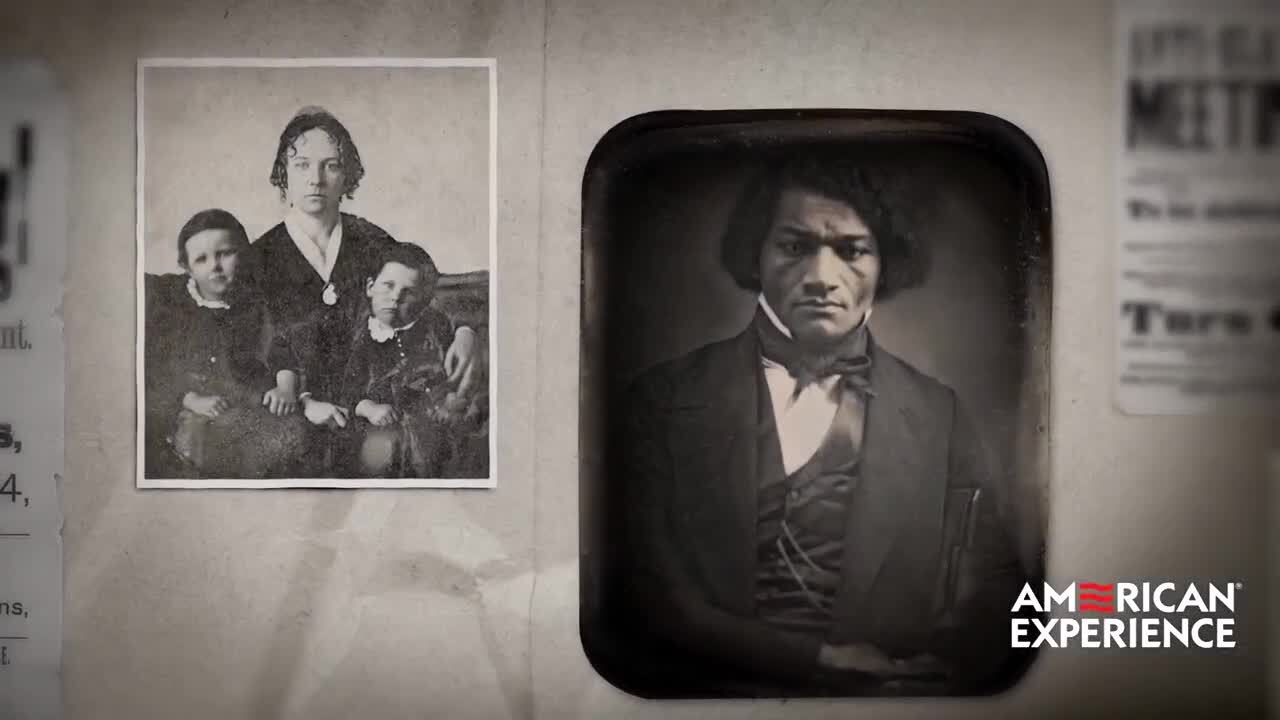

Women's suffrage found its first male champion in Frederick Douglass, who had escaped enslavement to become a leader of the abolitionist movement. From the abolitionist ranks also came the first generation of suffragists, Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, and Sojourner Truth; Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Sarah Remond, Susan B. Anthony-- women for whom the two causes at first were entwined.

[GUNFIRE]

When the conflict over slavery finally exploded into Civil War, the suffragists set their own agenda aside to help secure rights for those who'd been enslaved. Expecting, as Stanton put it, that "when the constitutional door is open, we will avail ourselves of the strong arm and the blue uniform of the Black soldier to walk in by his side." Their rallying cry now was, "Equal voting rights to all." Instead, under pressure from congressional Republicans, the party of Lincoln, Stanton and her friends were asked in 1869 to support the 15th Amendment, which extended federal protection for the franchise only to African American men.

The suffragists truly believed, perhaps naively, that once the war is over, all eligible citizens are going to get the vote. They are shattered when they're told that the nation cannot handle two great reforms at once. They can't swallow Black men getting the vote and women getting the vote at the same time.

Frederick Douglass says, I believe in women's suffrage. I always will. But the Black man needs it first. My people are being killed.

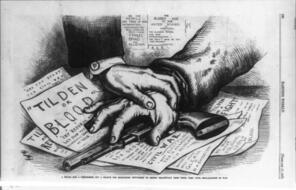

The question of compromise, once introduced, quickly became a wedge. "If you will not give the whole loaf of justice to the entire people," Susan B. Anthony told Douglass, it should be given to "the most intelligent and capable portion of women first." Elizabeth Cady Stanton was less civil. "Think of Sambo," she fumed, "who never read the Declaration of Independence or Webster's spelling book, making laws for educated, refined women."

Stanton and Anthony have constructed the debate around the vote as one that positions white women against African American men. Stanton, in particular, has made the argument that she will not see former slaves, the sons of slaves, enfranchised over elite, educated women. These are ideas that are not uncommon, but now racism is, sort of in a full-throated way, part of the deliberations.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

In the end, the fragile coalition forged by the Civil War was shattered by the terms of the peace-- and causes once regarded as compatible had been set in opposition, to be prioritized one over the other if expedient. As Frances Ellen Watkins Harper noted ruefully, "When it was a question of race, I let the lesser question of sex go. But the white women all go for sex, letting race occupy a minor position."