Responses to the 1930s Refugee Crisis

At a Glance

Language

English — USGrade

12Duration

One 50-min class period- The Holocaust

Overview

About This Lesson

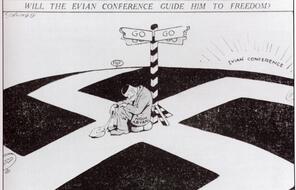

To dig deeper into the ethical and political dilemmas underscoring the Sharps’ story, students begin with an anticipation guide that explores complex questions of how individuals and nations respond to the needs of others. Then they learn the powerful concept of the “universe of obligation.” As they watch an excerpt from the documentary Defying the Nazis and read related primary sources, students use the notion of the universe of obligation to think critically about individual and collective American responses to the refugee crisis of the 1930s.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Extension Activities

Additional Resources

Resources from Other Organizations

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand