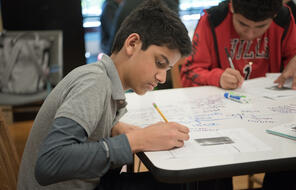

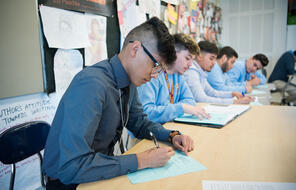

[JAKE MONTWIELER] I love Socratic seminars because it's giving students a chance to work together to really create knowledge. That's the joy of it. It's really an example of authentic learning. They are practicing the skill of seeing multiple perspectives by engaging with their classmates, who may see things a little bit differently. They're also practicing making a position with evidence. Because it's text-based, I'm hoping that they'll refer to that, refer to the text that we're using. It's challenging for eighth graders to do that. That's why we practice it a lot. Because I'm trying mostly to step out of the conversation, it's sometimes easy for students to not have a conversation so much as multiple monologues that are going on at the same time. One of my colleagues refers to this as parallel play. It's like kids in a sandbox who aren't really engaging with each other, but are doing their own task. What I've done, hopefully, to encourage a more authentic discussion is to encourage students to respond to each other with follow-up questions before they ask another question of the classmates. That's hard. Normally, as teachers, I think at our best teaching, we're always asking follow-up questions. Kids haven't practiced that, so even with reminders, sometimes that's hard to do. Through our Socratic seminar, I'm also hoping that students will reflect on a more general experience in human nature. When we are protected by darkness, when there is anonymity, it is easier for expressions of hatred and intolerance to come out. That's the experience of Henry Buxbaum in this lesson. And I think what students will connect to is to experiences online, right, where there's a similar darkness because you can post things anonymously and we can't see the effect of our actions. That's what happened on this train in 1923. And I'm hoping our students will see, oh, that's a similar experience to what I face when I'm texting today. As always with Socratic seminars, I want to give you a little bit of time to prepare. I have the reading here. It's just what I read, but I would like you to reread it. What is maybe helpful here is to find one or two phrases to just do a little box around. That's going to help us stay anchored in the text. So as you read it, just one or two phrases and you think, oh, that line is important. Just box it or star it or underline it. And then you're going to be writing your reactions, and then some open-ended questions. The best Socratic seminar questions do two things. First of all, they have multiple answers, right? They've got multiple different ways to answer. And then also, they're really anchored in the history and anchored in the text. So I want to encourage you not to do a lot of hypothetical questions. If you have one hypothetical question, one what if question, you know, what if the lights had been on, would things have changed, one is great. But then I really want to see if you can ask an open-ended question about that moment, about Henry's experience, about what this teaches us about Germany in the 1920s. I want to remind you that you are talking with each other, right? I'm really going to step out. I will start us with a question. You're running the show. Something that we've been working on this spring which is really important is building off of each other's answers. If someone offers an answer, I'd like the next couple comments to be comments about that answer or a follow-up question. OK? So we want to stick with one person's answer for a little bit. That's going to help us really get deep into this text. At the end of our seminar, as we often do, we're going to have a chance to give some shout outs. My first question is this. What does this story teach us about Germany in the early 1920s? [SPEAKER 1] They were using the Jewish people as an excuse for what was going wrong. They were trying to blame them for what happened in Germany. [JAKE MONTWIELER] Yeah. [SPEAKER 2] It could also show how unstable and divided the country-- the public was after World War I, because they're all torn on what happened, and all had mixed feelings about the new government and the old government, the monarchy. [SPEAKER 3] And it also says, that night there were seven or eight people in the dark fourth class compartment. It might show their social standing and their economic power. [SPEAKER 4] But I think part of the reason why they might have been blaming the Jews for all their problems was because the Treaty of Versailles forced Germany to accept all of the blame for World War I. So they didn't want that kind of guilt, so they probably might have turned to the Jews to kind of pass it on. [SPEAKER 5] I boxed probably more encouraged by the darkness than his own valor, suggested, let's throw the Jew out of the train. This really reminds me of current age, cyberbullying, like how everyone feels much more confident because nobody can see them or say anything against them. And I feel like that's directly related to that quote there. And I was asking, how would it change if the lights were on? I mean, I think he probably would've said something, but much less severe. [SPEAKER 6] If you say something directly to someone's face, you can't say something that harsh because you can see a person, you can see humanity in front of what you're saying it to. But if you say it like you can't see anything. In this, it was dark. If I say something to whoever, and I can't see them, I could say whatever. But if they're in front of me, and I can see them, then it would be really hard for me to say exactly what I would say if it was dark straight up to their face, looking them in the eye. [SPEAKER 7] In the text, it says "quickly, some of the others joined in." It seems almost as if they were kind of like, oh, well, yeah, I agree with you. But do you think they really agreed with the person who started off the conversation? [SPEAKER 8] I think it could have gone two ways, one being they wanted to get something out and say something, but since that one person went up and said, oh yeah, blah, blah, blah about the Jews, they're like, oh yeah, I want to say that, too. So then they jumped in, feeling like-- it's kind of like having bystanders and the bully perpetrator. [JAKE MONTWIELER] How so? Tell us a little bit-- [SPEAKER 8] Oh, like they feel more powerful that there are more people that agree with them and behind them, standing up to the point that they're saying. [JAKE MONTWIELER] So the crowd is significant here. [SPEAKER 9] Well, soccer is a very team sport, so normally, Henry and the person that were saying the vicious things would be working together. And then when the person was against him, it felt like he had no one there and he was isolated by himself. [JAKE MONTWIELER] Unfortunately, I want to move. And what I want to ask here is if we can offer some shout outs to people. That is, a comment that you thought was really thoughtful, a question that moved your thinking. And this one, if you can raise your hand, and then I will call on you for this. So Kiki, a shout out. [SPEAKER 10] I thought, Alex, when you did the connection of cyberbullying and the lights off, I thought that was really good. [SPEAKER 11] [INAUDIBLE] for raising that question, because I felt that it was a very important point to add soccer club to it. [JAKE MONTWIELER] Beautiful. Nice. Good snaps for everyone there. [SNAPPING FINGERS] I want to say something that you did really well during this Socratic seminar that I was particularly pleased about was using the text, that you guys really stayed rooted in the text, and a lot of you were quoting the text and then making inferences based on that. That's a great skill, right? We've been practicing it all year, but I was really pleased with how you did that today. This year, I've really focused on Socratic seminars. I've told kids this is a strategy that we're going to work on, so we've named them explicitly and named some expectations for them. Because it's a relatively small class, I'm still able to hear from most students during the seminar. I think you do miss what you would get from an inside/outside circle. You miss students who are doing a little bit more metacognition about the actual learning experience. I think that's OK because we have this experience of giving shout outs at the end, where they can reflect as a group and give some specific positive feedback to an individual. So I felt good about this lesson. I think that our seminar was pretty successful. Kids were able to build on each other's ideas. I was pleased with that. That was one of my goals. I was also happy about the way they were using the text, that they stayed pretty grounded in what Henry Buxbaum had written, that they were able to reference it sometimes directly, and make some inferences on it. So that felt pretty successful.