Taking Austria

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- The Holocaust

In his 1925 book Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler wrote about Austria, his country of birth:

German-Austria must return to the great German motherland, and not because of economic considerations of any sort. No, no: even if from the economic point of view this union were unimportant, indeed, if it were harmful, it ought nevertheless to be brought about. Common blood belongs in a common Reich. As long as the German nation is unable even to band together its own children in one common State, it has no moral right to think of colonization as one of its political aims. Only when the boundaries of the Reich include even the last German, only when it is no longer possible to assure him of daily bread inside them, does there arise, out of the distress of the nation, the moral right to acquire foreign soil and territory. 1

In July of 1934, a pro-Nazi group tried to overthrow the Austrian government. The coup was planned in Germany, with Hitler’s approval and assistance from German officials. But although the group assassinated Austria’s chancellor, the attempt failed when Austrian military leaders did not support the coup as the Nazis hoped. 2 Then, despite his previous words and actions, Hitler said in a May 21, 1935, speech to the Reichstag: “Germany neither intends nor wishes to interfere in the internal affairs of Austria, to annex Austria, or to conclude an Anschluss [union with Austria].” 3

But on February 12, 1938, Hitler changed course again. He arranged a meeting with the new Austrian chancellor, Kurt von Schuschnigg, who was appointed after his predecessor’s assassination. Hitler demanded that von Schuschnigg appoint members of Austria’s Nazi Party to his cabinet and give full political rights to the party or face an invasion by the German army. Fearful that Hitler intended to take over Austria, von Schuschnigg called for a national plebiscite, or vote, to take place on Sunday, March 13, so that Austrians could decide for themselves whether they wished their nation to remain independent or become part of the Third Reich. When Hitler heard this news, he decided to invade Austria immediately to prevent the vote. By Friday morning, March 11, von Schuschnigg was aware of the coming invasion. That afternoon, he canceled the plebiscite and offered to resign to avoid bloodshed. Hitler immediately demanded that the president of Austria, Wilhelm Miklas, appoint an Austrian member of the Nazi Party as the nation’s next chancellor. When the president refused to do so, Hitler ordered that the invasion begin at dawn the next day.

German Military in Austria, 1938

German Military in Austria, 1938

The German military parades through Vienna on March 15, 1938, after the Anschluss.

Around midnight, the president gave in and named Hitler’s choice as chancellor. Nevertheless, early on Saturday, March 12, German soldiers in tanks and armored vehicles crossed the border into Austria, encountering no resistance.

The Nazis justified the invasion by claiming that Austria had descended into chaos. They circulated fake reports of rioting in Vienna and street fights caused by Communists. German newspapers printed a phony telegram supposedly from the new Austrian chancellor saying that German troops were necessary to restore order.

As his troops rushed toward Vienna, Hitler decided to accompany them to his birthplace at Braunau am Inn on the south bank of Austria’s Inn River and then on to Linz, where he had attended school. There he called for an immediate Anschluss. The next day, Austria’s parliament formally approved the annexation. Austria no longer existed as a nation; it was now a province of Germany.

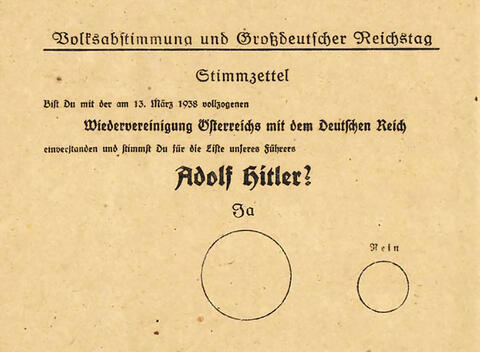

German Voting Ballot, 1938

German Voting Ballot, 1938

On April 10, 1938, Austrians were asked whether they supported the March 13 Anschluss. 99.75% of voters said that they supported Germany’s annexation of Austria into the Third Reich.

After returning to Germany, Hitler issued a new call for a plebiscite on the annexation of Austria. It took place on April 10 under the supervision of the German army. That day, more than 99.75% of Austrian voters supported a union with Germany. Historian Evan Burr Bukey suggests four reasons “for the euphoria with which most Austrians greeted the loss of their country’s independence”:

First, there can be no doubt that the initial enthusiasm was both genuine and spontaneous . . . Second, it is clear that the populace was profoundly relieved that bloodshed had been avoided . . . The sight of well-equipped Landsers [German soldiers] marching through the country revived memories of wartime solidarity and evoked a sense of satisfaction that the humiliations of 1918 had at last been overcome. Third, nearly all hoped for a dramatic improvement in the material conditions of everyday life; most Austrians were aware of Hitler's economic achievements and had good reason to believe that their expectations would soon be fulfilled. Fourth, there can be little doubt that millions of people welcomed the Anschluss as a chance to put an end to the so-called Jewish Question. The antisemitic violence that followed . . . was perpetrated by the Austrian Nazis and their accomplices, not by the German invaders. That the new regime openly sanctioned persecution and Aryanization, in other words, could only enhance its popularity. 4

Most Germans were also supportive: Bukey notes that “even sections of society that had been cool towards Hitler up to this point, or rejected him, were now carried along by the event and admitted that Hitler was after all a great and clever statesman who would lead Germany upwards again to greatness and esteem from the defeat of 1918.” 5 Earlier, Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy, had publicly defended Austria’s independence. Now he backed Hitler. Other world leaders were silent; they seemed to feel that Austria was not worth fighting for. In Britain, for example, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain reminded Parliament that their country had no treaty obligations with Austria. Only Winston Churchill, then a member of Parliament, disagreed. In a speech to the British government, he declared:

The gravity of the event of March 12 cannot be exaggerated. Europe is confronted with a program of aggression . . . unfolding stage by stage, and there is only one choice open, not only to us but to other countries who are unfortunately concerned—either to submit, like Austria, or to else take effective measures while time remains to ward off the danger and, if it cannot be warded off, to cope with it. 6

Connection Questions

- What is Hitler’s reasoning, at this point in history, for incorporating Austria into the German Reich? In the excerpt from Mein Kampf, what is the larger plan that he suggests the Anschluss is part of?

- Why did Hitler want to prevent the vote planned by von Schuschnigg in March? Why did he then plan his own vote in April?

- Why did so many Austrians support the Anschluss? Why did Germans support it?

- Winston Churchill warned that it was time for countries to take “effective measures” to respond to Germany’s aggression. What choices do you think were available to other countries? What might have been among these countries’ reasons for not intervening as Hitler took over Austria?

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Taking Austria," last updated August 2, 2016.