Breadcrumb

Verifying the Story

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Civics & Citizenship

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

- Racism

Verifying the Story

[MUSIC PLAYING]

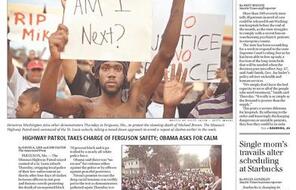

A local 18-year-old is shot and killed by police in Ferguson. Family members, joined by protesters, are demanding answers.

Johnson says him and Brown were scared and ran away from the officer.

He shot again. And once my friend felt that shot, he turned around and he put his hands in the air. And he started to get down. But the officer still approached with his weapon drawn. And he fired several more shots.

No justice, no peace.

Instantly, hundreds gathered, angered and saddened by what they call a complete overreaction by the officer. Now, a family is demanding answers.

[PAT GAUEN] From my perspective, the hardest thing to verify, especially early on, was some narrative from the police side of what happened in Ferguson. The police said so little early on that when we were trying to balance a story, critics said they saw the police officer chase him down the street. They saw him stand over Michael Brown. They saw him shoot Brown while he was pleading for his life. We didn't have anything to counter that. The police weren't saying anything.

[GILBERT BAILON] The people who were protesting used the "hands up" as their slogan, as their cause. And it became very, very well known throughout the world and the nation, eventually. Later in the investigation, what the official investigation was, he did not have his hands up when he was shot. But we reported what witnesses said who did. So there's conflicting information.

[PAT GAUEN] I think it gave us a lopsided story for rather a while. And that was very frustrating. And we had well-sourced reporters doing what they could to bear down and get more of the police side, and finally did.

And within about six days, when we learned more about the Michael Brown strong-arm robbery that had preceded the encounter with Darren Wilson, we sort of got at least an emergence of the picture from the law enforcement side, and one that would later be pretty much verified by the grand jury investigation and the Department of Justice investigation.

But that story was really late to the coming. And by that time, people had formed their opinions. It was very easy to dismiss a police account six days later. Well, you finally got your story in order, cops. And why should we believe you now? If you knew this back on Saturday or Sunday, why didn't you say it on Saturday or Sunday?

[ALICE SPERI] Some of the things I read about Ferguson before I got there were like, this vigil for this slain teenager turned into a mob. But I'm like, what does mob mean, really? And so I was very mindful not to use that language.

A lot of people showed the images of the looting. Somebody had broken into this liquor store. And we started talking to the kids at the door. And if you looked at it from a distance and just filmed it, it would have looked like they just broke in and they're watching for their friends that are inside. And if you talk to them, it's kids from the neighborhood that were trying to get them just out. There's no way you would have known that if you didn't question the scene.

So I think we all make assumptions all the time. And especially in a situation like that, it's very easy to go for what you think you know. And so being mindful that that's an issue and trying to always ask is a good step to undo the bias in a way.

Even a witness, I mean I talked to a lot of the people that were on the scene of the murder, right after, and then one guy that was actually live tweeting Mike Brown's murder. And he doesn't fully know what happened. He took pictures of it. He saw it. And he'll tell you, this is what I saw. This is what I didn't see.

And so there is no-- there is not one source that has it all that you need to get, and that's it. That's your truth. That's your story. You want to put the puzzle together with all these different pieces.

[WESLEY LOWERY] Many times, verifying information in Ferguson was extremely difficult. This was a very fast-moving story, with intense national interest, happening not even in a major city, but in a suburb of a major city. So there wasn't a lot of information channels. This wasn't a place we were particularly well-sourced initially.

And on top of that, it was just so hectic and so chaotic. You had multiple police departments involved, city officials, state officials, potentially federal officials, with information leaking from all sorts of corners.

[DENEEN BROWN] The challenges that I had in Ferguson was, I was on the street reporting, so I was in the midst of the protest. And events were happening pretty quickly. And as you know, it's a really competitive news cycle. So I needed to get information to the desk as soon as possible.

Much of my reporting was raw. I was there on the ground. I was an eyewitness to some of the events that happened. So for the events that happened where I was an eyewitness to was not particularly challenging to check it out, because I was there, which is, I think, the best form of journalism.

But for information that I was gathering by phone or from sources, I would send that information to the desk. And they had reporters here by the phones. And they were able to check out the facts before they were printed.

[KEVIN MERIDA] When we're doing breaking news, usually some of the best and quickest information you can get is you're having some of our great researchers find-- they're looking for leads everywhere. They're looking through databases. They're trying to find phone numbers. They're trying to find records. They're trying to find clues, decrees, orders. They're trying to find-- and then people here pursue those tips.

[KRISSAH THOMPSON] We had trained reporters who were there on the scene. We had others who were at the police station who had gone out to talk to and find the person who did the local autopsy. Those are the kind of things that you're not going to just see flowing across your Twitter feed. But when you come to the Post, that it's all stitched together for you. And it'll give you a broader picture of what's happening.

[ALICE SPERI] Verification is basically asking as many questions as possible to as many people as possible that have a relevant take on what happened, that have witnessed it directly, that have a direct experience with it, or an expertise that's relevant, and then kind of putting all that information together and clearly telling, this is what I know, this is what I don't know, this is how I know it, this is where it comes from.

And verification is a complex process. So it's a puzzle. You put together the different pieces. Everything you see is not necessarily all there is to be seen. Or you're not necessarily interpreting it correctly.

At the same time, when you talk to somebody and they tell you what they saw, that's also not the full picture. And you never have the full picture. The idea of our job is you never know what the full story is. And nobody really ever knows what the full story is.

[GILBERT BAILON] Sometimes it's up to a reader to look at this information and say, who's telling the truth? Do I believe this person? Do I believe this information? It's up to individuals to make those conclusions.

[DENEEN BROWN] I think readers, people who consume social media, should try to verify what they see on tweets or on Facebook. I often go to main news sites to see whether they're reporting the same information that I'm seeing on Twitter or Facebook.

So I think that that would be a good lesson for the public. If you see something on Twitter that appears questionable, go to washingtonpost.com or the New York Times, Wall Street Journal-- reporting that information, because reporters for those newspapers are required to verify that information as much as possible before publishing it.

[GABRIELA AKRAP] So if CNN is saying one thing, I kind of go check out what the other news sources are saying, just to make sure it's all kind of in the same spectrum and not something super crazy, because then it's probably, it was just kind of a not very credible thing.

[GILBERT BAILON] What we can't always say is, this is the one truth, because that's not what we do. We don't tell one truth. We try to tell as much things and as many things that are truthful.

[KRISSAH THOMPSON] Our approach for this story, and any major moving story, is that you just continue to report the story. And it evolves over time. And the truth becomes clearer.

One of the things that the public often does, and that any reporter who is on a story for a long time can relate to, is that you want to drop out of the story and sort of move on. You feel like you know what happened, and you've made your opinion, and it's over. And it does keep evolving. And layers keep pulling back.

I would just encourage people to stay involved and engaged in stories. If they've invested in it in the beginning enough to sort of form an opinion, then be open to changing dynamics on the ground and for new information being revealed to sort of influence what they think.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Verifying the Story

You might also be interested in…

#IfTheyGunnedMeDown

The Impact of Identity

The Power of Images

Preparing Students for Difficult Conversations

Social Media and Ferguson

Verifying Breaking News

Facing Ferguson: News Literacy in a Digital Age

Reflecting on George Floyd’s Death and Police Violence Towards Black Americans

Responding to the Insurrection at the US Capitol

The Hope and Fragility of Democracy in the United States

What Happened During the Insurrection at the US Capitol and Why?

The Importance of a Free Press