Western Imperialism and Nation Building in Japan and China

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

Grade

9–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Genocide

Overview

About This Lesson

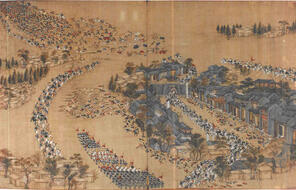

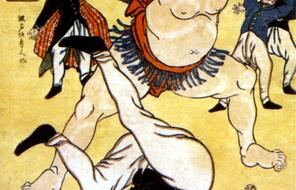

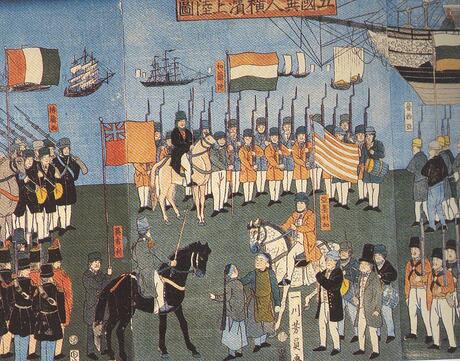

In the opening lesson of this unit, students will begin to explore the factors that contributed to Japan’s invasion of China during World War II and the occupation of Nanjing. Through an exploration of primary sources, including a Japanese woodblock print and a political cartoon, they will be introduced to the history of Western imperialism in East Asia and how it influenced both the identities and ambitions of Japan and China. Students will also conduct a comparative analysis of timelines depicting major events in China and Japan during the nineteenth century, beginning to explore the two countries’ divergent responses to Western imperialism and how these developments affected the complexity of nation-building efforts in China and Japan. This lesson and the following one, on the rise of nationalism and militarism in Japan, are both critical for understanding the complex factors that led to the Japanese war crimes known today as the Nanjing atrocities.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before you teach this lesson, please review the following guidance to tailor this lesson to your students’ contexts and needs.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Assessment

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Western Imperialism and Nation Building in Japan and China

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand