The Legacy of a Witness

At a Glance

Subject

- History

- Social Studies

- Genocide

Armin Wegner personally witnessed the brutality of the Armenian Genocide, and it changed him forever. After he first learned about the atrocities he risked his life to document the destruction of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire.

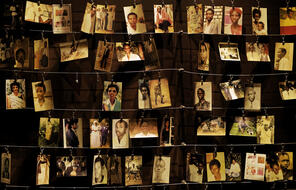

Wegner was born in Wupperthal, Germany, in 1886 and died in Rome, Italy in 1978. As a young man with the German army, he witnessed the Armenian Genocide and took graphic photographs of what he saw. For the rest of his life, he devoted his efforts as a writer, photographer, and poet to human rights.

At the outset of World War I, Wegner enrolled in the army as a volunteer nurse in Poland. When Turkey joined the alliance with Germany, he was sent to the Middle East as a member of the German Sanitary Corps. Wegner used his leave in the summer months to investigate rumors about the Armenian massacres. Horrified by what he witnessed, Wegner went to work. Serving under German Field Marshal von der Goltz, commander of the sixth Ottoman Army in Turkey, he traveled throughout Asia Minor, photographing the Armenian deportations and the unburied remains of the dead. Deliberately disobeying orders meant to prevent news of the massacres from spreading, Wegner arranged for evidence of the genocide, including photographs, documents, and personal notes to reach contacts in Germany and the United States. Before long, Wegner’s mail routes were discovered, and the Turkish government asked the German army to place him under arrest.

Reassigned to the cholera wards, Wegner became seriously ill the fall of 1916 and was sent from Baghdad to Constantinople in November 1916, all the while hiding photographic images of the atrocities in hisnbelt. Wegner was recalled to Germany in 1916. Back home he continued to raise consciousness about the Armenian massacres. In 1919, Wegner published his eyewitness accounts of the atrocities in The Way of No Return: A Martyrdom in Letters.

By that time, the map of Europe and Asia was very different from what it had been before the war. The large multinational empires had been broken apart, and new independent nation states were created in their place. The Armenian Republic in Russian Armenia was one of these new states.

I appeal to you at the moment when the Governments allied to you are carrying on peace negotiations in Paris, which will determine the fate of the world for many decades.

But the Armenian people is only a small one among several others; and the future of greater and more prominent states is hanging in the balance. And so there is reason to fear that the importance of a small and extremely enfeebled nation may be obscured by the influential and selfish aims of the great European States, and that with regard to Armenia there will be a repetition of neglect and oblivion of which she has so often been the victim in the course of her history….

In the Berlin Treaty of July 1878, all the six European Great Powers gave the most solemn guarantees that they would guard the tranquility and security of the Armenian People. But has this promise ever been kept? Even Abdul Hamid’s massacres failed to refresh their memory, and in blind greed they pursued selfish aims, not one putting itself forward as the champion of an oppressed people. In the Armistice between Turkey and your Allies, which the Armenians all over the world awaited with anxiety, the Armenian Question is scarcely mentioned.

Shall this unworthy game be repeated a second time, and must the Armenians be once more disillusioned? The future of this small nation must not be relegated to obscurity behind the selfish schemes and plans of the great states. . . .

Mr. President, pride prevents me from pleading for my own people. I have no doubt that, out of the depths of its sorrow, they will find the force to co-operate, making sacrifices for the future redemption of the world.

But, on behalf of the Armenian Nation, which has been so utterly humiliated, I venture to intervene, for if, after this war, it is not given reparation for its fearful sufferings, it will be lost forever. 1

By 1921, the Armenian Republic was lost. When Kemalist forces invaded the small republic, its leaders turned to the new Russian Bolshevik government for protection. Just a few years later, Wegner reeled in horror when the Nazis came to power in his own country, bringing with them a vile racism that Wegner found familiar. In the months after Hitler became chancellor of Germany, anti-Jewish legislation swept the country. Unable to remain only a witness, Wegner delivered a letter, through intermediaries, to Hitler pleading for an end to the persecution of the Jews to save the soul of Germany. Nazi officials had Wegner arrested but it did not silence him. He continued to try to speak out to protect the Jews from the brutal end suffered by the Armenians he had photographed.

In 1966, on the fifty-first anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, Wegner described the frustration of being a witness to an atrocity that had been nearly forgotten.

This is what happened to the witness who tried to have their tragedy and their end known. He continued to bear the burden of his promise to remember the dead once back in the West. But no one listened anymore.

Fifty years have passed. The people of even larger nations have experienced great suffering. The witness remains, full of shame and feeling a little guilty for he has seen things that one can see without risking one’s life. Does this not perhaps mean that he must die like one who has seen the face of God?

There is silence all about him. In whatever direction he turns, he knocks on closed doors. “We have our own sorrow!” they think or say. “We bear the tragedies of our own people. Why should we torment ourselves with the pain of others, long forgotten?”

They want to live without worry or sorrow, and go through life knowing nothing about the violence and troubles of the preceding generation. At the beginning of the Twenties, when the witness of these horrors foresaw that the same thing could occur in the West, and illustrated what he had seen with numerous photographs and all the documentation that he could collect from the extermination camps, those that came to know of these things in Germany and in neighboring countries were seized with fear but thought, “The Arabian desert is so far away!” 2

Connection Questions

- Wegner describes himself as a witness to the Armenian Genocide. What are the responsibilities of people who have witnessed an injustice? When are they relieved of those responsibilities?

- Wegner’s photographs are housed at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Samples from the collection may be viewed online at http://www.armenian-genocide.org/photo-wegner/index.htm. After viewing the photographs, discuss their impact. How do they add to your understanding of the genocide?

- Wegner tried to save Jews from the same end that met the Armenians. Imagine if the world had paid attention. What lessons should have been learned from this history?

- How does Wegner describe the world’s responsibility towards the Armenian people to President Wilson? What arguments does he make for US intervention? Which do you personally find most convincing? Least effective? Which arguments do you imagine would resonate with the President?

- Wegner writes about the reactions he gets when he reminds people of the treatment of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. People responded, “We have our own sorrow.... We bear the tragedies of our own people. Why should we torment ourselves with the pain of others, long forgotten?” How would you answer those comments?