Women Rise Up Against Apartheid and Change the Movement

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

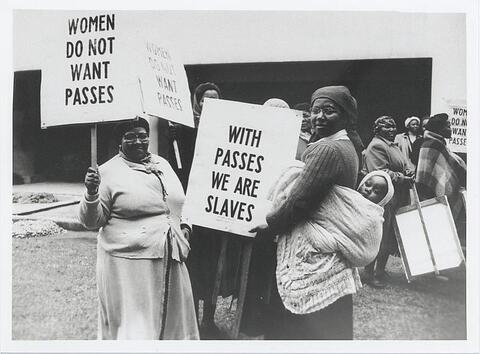

Women Resist Pass Laws

Women Resist Pass Laws

A group of women hold signs in demonstration against the pass laws in Cape Town on August 9, 1956, the same day as the massive women’s protest in Pretoria.

Since the early twentieth century, African women actively opposed the pass laws restricting the movement of Africans. The women understood that these laws would tear African families apart, codifying where Africans could work and live and with whom. Even in the early 1900s, Black women successfully prevented proposed legislation that would require them to carry passbooks. In 1953, however, their fear was close to becoming a reality, as the government announced that it would soon impose pass laws restricting the movement of Black African women.

In the 1950s, the African National Congress turned to grassroots organizing to work against increasing racial restrictions. Women played a key role, encouraging the larger democratic movement to include women’s issues and fostering the leadership of women. The newly formed Federation of South African Women began organizing women of all races to fight together for equality. The federation started locally but spread throughout the country, organizing from street to street and within trade unions. These grassroots efforts led to many local demonstrations and culminated in the women’s march on Pretoria, the capital, in 1956. Yet their work did not stop the government from extending the pass laws to African women.

One of the leaders was Frances Baard, a longtime organizer with a reputation for perseverance. After the women’s march, the government charged her with treason but was unable to prove its case. A few years later, the government struck again, imprisoning her for five years. In this excerpt from her autobiography My Spirit Is Not Banned, she offers a firsthand account of the women’s march and the particular challenges Black African women faced under apartheid.

1956 Women's March, Pretoria

1956 Women's March, Pretoria

Female demonstrators march to the Union Buildings (official seat of the South African Government) during the 1956 Women’s March on August 9, in opposition to the 1952 pass laws.

The Women’s March

For a long time the women were not proper members of the ANC [African National Congress]. They only changed that in 1943 when the women were allowed to join properly. That was when the Women's League started. So it was a very big thing for us to organize the women like that.

We used to go out in the evening mainly when everyone is home from work, and we walk from house to house in the [segregated township] location and talk to the women. We knock on the door, and when they open we tell them we are from the Women's League and can we talk to them. We talk about the problems they have—maybe it's high rent or no money for food. The women were always worried about their sons and their husbands being arrested for passes all the time. And they are worried maybe they will lose their houses. Also there were things that the people as a whole did not like, things that were very strong in their lives like housing and jobs and passes (some people could not get jobs because their passes were not right) and we used to talk to the women about these things too. The women had lots of problems. It is always the women who are trying to feed the family and look after them, and there is too little money and so on. We tell them how we want to do something about these troubles, and how they must join us so we can be strong and go to the authorities about all these things. After a while we had a group of women behind us who all wanted to help. Then we started to have big meetings. . . .

But us women, even when we did things like this, we never used to work by ourselves, because we were part of the ANC as a whole. We used to have our own meetings, just the women, and talk about what we wanted to do and how to do it. Then we would go to the general meeting [of the ANC] and tell them, "Such and such a thing is so and so, and we want to do this and this."

And we would tell them exactly what we wanted to do to put this thing right. We would discuss it all together at the general meeting and decide on it, and we would get a mandate from them. . . .

We women had a lot of problems at that time which the men didn't have to worry about. I remember there was one thing which we all used to worry about. If a woman's husband died they used to chase her out of the house, or tell her to get another husband, because only married women can have houses. I had a case with one woman who came to me one day. Her husband had just died and they chased her out of the house she lived in. She came to me and told me how they chased her out. I went and spoke to them and said, "But how can you let a woman go out of her house and yet she's got children? Where must she go?"

Then they tell me, "No, she must go back to the kraal [a cattle pen]; there will be a husband waiting for her there." . . .

The Federation [of Women] decided that we should protest to Strijdom, the Prime Minister, that we didn’t want these passes. . . . [W]e would send thousands of women from all over South Africa, black and white. . . . So each of us in her own place had to organize the women for this protest. We only had a few months to prepare for this but we wanted to send many, many women. . . . But before we went to Pretoria [to the Prime Minister’s] we got all the women who couldn't go to sign petitions to say that they also didn't want these passes. . . .

It is two days by train [for our group] from Port Elizabeth to Pretoria. Two days on the train sitting in the railway carriage, singing all the way. First we went to Johannesburg and we slept the night in Soweto, and then the next day, it was August 9th, we went to Pretoria. Some took buses, some trains, some taxis, anything to get to Pretoria. . . .

Then we all walked into the yard of the Union [government] Buildings and we waited there for all the women coming from other places. . . .

It was about 20 000 of us altogether! . . .

Eight of us took all those petitions that had been signed, piles and piles of them, and we marched up to Strijdom's office to give them to him. The secretary told us that Strijdom was not there and that we were not allowed in anyway because we were black and white together. . . .

Then we walked outside again and joined the other women who were waiting in the amphitheatre. All the women were quiet. 20,000 women standing there, some with their babies on their backs, and so quiet, no noise at all, just waiting. What a sight, so quiet, and so much colour, many women in green, gold and black [ANC colors], and the Indian women in their bright saris! Then Lilian [Ngoyi, ANC leader] started to speak. She told everyone that the prime minister was not there and that he was too scared to see us but that we left the petitions there for him to see. Then we stood in silence for half an hour. Everyone stood with their hands raised in the salute, silent, and even the babies hardly cried. For half an hour we stood there in the sun. And not a sound. Just the clock striking. Then Lilian started to sing and we all sang with her. I'll never forget the song we sang then. It was a song especially written for that occasion. It was written by a woman from the Free State. It went: "Wena Strijdom, wa'thinthabafazi, wathint’imbokotho, uzokufa!" That means: "You Strijdom, you have touched the women, you have struck against rock, you will die." Of course he did die, not long after that. 1

Connection Questions

- What insights does Baard offer about the particular challenges faced by women under apartheid?

- In the 1950s, the apartheid government seemed impregnable. Effective organizing in any country requires deciding how to get people to participate, to march, to speak, and to encourage others to organize in their own communities. Some describe that work as grassroots organizing. What approach did Baard take? Did she start by talking about the pass laws? How did she get around the widespread attitude, especially prevalent under apartheid, that “what I do won’t matter because ‘They’ are too powerful”?

- Twenty thousand women of all races participated in the 1956 women’s march. Despite their numbers, the prime minister, J. G. Strijdom, refused to meet with them and later signed into law the legislation they were protesting. How would you evaluate the effectiveness of this march?

- Frances Baard’s recollection of the march is laced with hope. Where does such hope come from? How is it maintained?

- 1Frances Baard and Barbie Schreiner, My Spirit Is Not Banned (Harare: Zimbabwe Publ. House, 1986), 314–19.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “Women Rise Up Against Apartheid and Change the Movement,” last updated July 31, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.