Youth on the Margins

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- The Holocaust

Changes at School under the Nazis

In her book School for Barbarians, Erika Mann describes how greeting others with the Nazi salute and the words “Heil Hitler” became a common, constant practice in Germany, infusing daily life and social interactions with an expression of political loyalty (see reading, “Heil Hitler!”: Lessons of Daily Life). The “Heil Hitler” greeting was also an important part of the school day, posing difficult and even dangerous dilemmas for some students.

When Elizabeth Dopazo and her brother were very young, their parents were sent to concentration camps because of their religious beliefs; they were Jehovah’s Witnesses whose faith required that they pledge allegiance only to God. Jehovah’s Witnesses therefore refused to say “Heil Hitler” as a matter of religious conviction. After their parents were arrested, seven-year-old Elizabeth and her six-year-old brother went to live with their grandparents. Elizabeth later recalled:

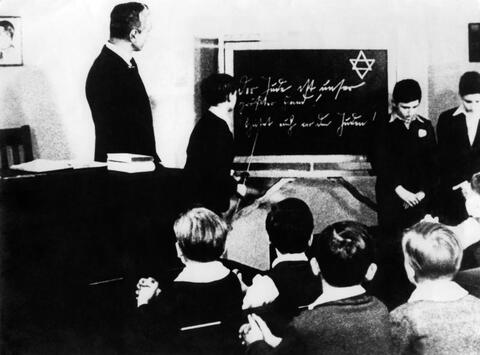

Race Science Class

Race Science Class

While this classroom studied “race science,” Jewish students were forced to stand at the front of the room. The blackboard says, “The Jew is our greatest enemy.”

We had to quickly change our way of speaking so maybe we wouldn’t be so noticeable. In school right away it started, you see. We had to raise our right arm and say “Heil Hitler” and all that sort of thing and then we didn’t do it a few times. A few times was all right. You can drop a handkerchief, you can do a little something, but quickly they look and they say, “Ah, you’re different and you’re new in the school.” So you’re watched a little more closely. You might get one or two children who’d tell on you but it was rare. The teacher would bring you to the front of the class and say “Why don’t you say Heil Hitler?” and you were shaking already because you knew, unlike other children, if you told them the real reason there’d be trouble. For us to say “Heil Hitler” and praise a person would be against our belief. We shouldn’t because we had already pledged our allegiance to God and that’s it. So we could stand and be respectful to the government, but we were not to participate in adulation for political figures. . . .

My brother and I talked about all these things at home after school. We had a little attic we used to go in and discuss what would be best. We grew up very fast. We never really had a childhood. . . .

Later, around age twelve or thirteen, we joined the Hitler Youth, which we actually didn’t want to do, but the Gestapo came to my grandparents’ house, just like you’ve seen in the movies with the long leather coats on and they stood at the front door and they were saying, “Your grandchildren have to join the Hitler Youth and if they don’t by Thursday we will take stronger measures.” After they’d left we told our grandparents we’ll join tomorrow, even if we hate all that stuff. They agreed we’d better do it and we very quickly donned those uniforms. . . .

As time went on, my brother, when he was thirteen or fourteen, sort of was swayed. You know, you have to believe in something. He wanted to be a German officer and said our father had been wrong all along and that we went to the dogs for our father’s beliefs. He [our father] died for his ideals and where are we? [My brother] was very angry. I was too, but not as much. I was torn between what would be the good thing to do and what would not. . . .

We were not allowed to go to higher education because we were a detriment to others. So you can image how he felt when the war was finished. He was all disillusioned and shattered. 1

Daily life in school was even more difficult for a boy named Frank, one of two Jewish students in a school in Breslau in the mid-1930s. He recalled:

People started to pick on me, “a dirty Jew,” and all this kind of thing. And we started to fight. . . . There was my friend, and he was one class above me, he fought in every break. . . . I started to fight, too, because they insulted too much or they started to fight, whatever it was.

We were very isolated, and one order came after another. . . . [One] order says all Jews must greet with the German greeting. The German greeting was “Heil Hitler” and raising your hand. Then the next order came out, and it says the Jews are not allowed to greet people with the “Heil Hitler” signal. Okay, so, in Germany you had to greet every teacher. When you see a teacher on the street, you had to respect them and you had to greet him—you had to bow down. . . .

Now we were in an impossible situation, because when we went up the stairs and we saw one teacher, and we said “Heil Hitler.” And he turned around. “Aren’t you a Jew? You’re not allowed to greet me with ‘Heil Hitler.’” But if I didn’t greet him at all, then the next teacher would say “Aren’t you supposed to greet [me with] ‘Heil Hitler’?” And this was always accompanied with a punishment. . . . Not all of them but some of them, the teachers that knew me and would pick on me—they’d punish me, put me in a corner, or humiliate me in one way or another. . . .You had to raise your hand and salute when the flag passed and Jews weren’t allowed to do it. . . . If you don’t salute, you immediately were recognized as a Jew, and you really were left to the mercy of the people who saw you, what they would do with you. They could perfectly well kill you on the street and, you know, nobody really said anything because there was no such thing as a court and after all, it was only a Jew. . . . We were at the mercy of people. 2

Connection Questions

- What dilemmas did Elizabeth Dopazo, her brother, and Frank face? How did they respond to those dilemmas? What choices were available to Elizabeth that were not available to Frank?

- Compare and contrast the experiences of Hans Wolf and Alfons Heck (see reading, Joining the Hitler Youth) with those of Elizabeth and Frank described in this reading. Were there any similarities? What are some of the key differences? How were these children affected by growing up in Nazi Germany in the 1930s? Do these readings express experiences and emotions that might also be typical of children everywhere?

- Do you think it is more important for teens to feel as if they belong than for people of other ages to feel that way? Why or why not? Why might the experience of being an outsider be more painful for a teenager than for others?

- 1Elizabeth Dopazo, “Reminiscences,” unpublished interview, 1981, Facing History and Ourselves Foundation.

- 2Childhood Experiences of German Jews (New Haven, CT: Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, ca. 1987), VHS.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Youth on the Margins," last updated August 2, 2016.