First Days

What did the first steps of “assimilation” look like in practice? How did the schools begin to break students’ connection to their indigenous communities?

A typical first day at a residential school consisted of a removal of indigenous identity and an introduction to the new rules, regulations, and lifestyle to which the children would have to adhere. The next passage is from Albert Canadien’s From Lishamie, in which he recounts his first day at Fort Providence Catholic School.

I wasn’t afraid up to this point, but the sudden appearance of the Sisters did frighten me. Before I could think, my mother let go of my hand and the Grey Nuns guided me through into the parlour. The reality hit me: I was being taken away from my parents! I started crying and tried to hang onto the door frame as the Sisters pulled me away. Trying her best to sooth me, my mother kept promising she would come back and visit us soon. By this time, my sister had already been led away. She had been here before and knew what was expected of her, so she picked up her bag and followed one of the Sisters to the girls’ section of the building. I’m sure she heard my cries and screams. . . .

I spent my first day at the residential school with the other new boys. Some of us were silent and scared, with tears in our eyes and not knowing what to do. Some of the other boys were sobbing uncontrollably. The two Sisters who were supervising the boys gathered us on the first floor of the building in a large room with benches along the walls. This was the boys’ recreation room. From there, we were led in single-file upstairs to a large dormitory on the second floor and were each assigned to a bed. One of the older boys, who had been through residential school before, acted as our interpreter. We were told to undress, put our clothes on our bed and get ready for a bath.

Once in the bathtub, the Sister poured a green-coloured liquid onto our heads and bodies, and we washed ourselves. Our clothes and other personal belongings were taken away and we were all given denim coveralls. We were to wear these at play and at work for the duration of our stay at the residential school. . . .

When the Sisters returned, one of them motioned for us to get into a single file again. Then we followed the other Sister out of the room and downstairs to the basement level for supper.

The dining room was a large, open area. A piano or organ sat against the wall in the middle of the room. This more or less indicated the separation point between the boys’ and girls’ dining areas. The girls’ designated area was on one side of the room and the boys’ area on the other. We sat on benches at long tables. I looked up as the girls entered their dining area and tried to catch a glimpse of my sister, but I didn’t see her. I turned my gaze to the enamel plate in front of me on the table. That enamel plate also served as a bowl for soup and porridge. I couldn’t eat much because I had a lump in my throat. I kept thinking of my parents, getting very homesick, and I started to cry again. The Sisters didn’t pay too much attention to me at that time, maybe because I was new to the ways of the residential school. They also knew I was there to stay no matter what.

After supper, we all stood up and said grace, just like we had done before supper. Once again, I didn’t understand what was being said. I was to learn and memorize this meal prayer both in French and English. Later on, we even sang grace in French before meals. Whether we said grace or sang grace depended on the Sister supervising at mealtime.

Bedtime that first evening was the hardest for me. I was used to sleeping an arm’s length from my dad. But tonight I would sleep alone in a strange place and it scared me. The dormitory was not that big, but to a small, seven-year-old, it was huge and intimidating. The walls and the ceiling of the dormitory appeared to be very high, much higher than the walls of our log house back home. It was a big change from our log house in Lishamie to the nuns’ big house. 1

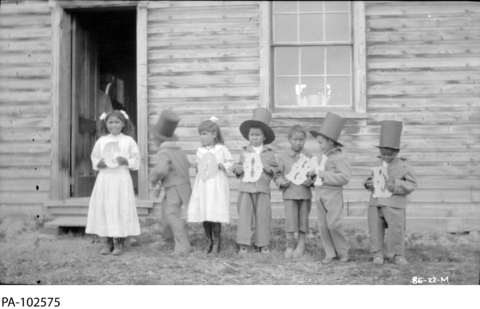

Students at the Fort Simpson School in the Northwest Territories in 1922 hold up letters that spell “Goodbye.” For most students, entering a residential school meant saying goodbye to their families, language, and culture.

In her book about the experience of the Mi’kmaq children at the residential school at Shubenacadie, Isabelle Knockwood reports on this moment of transformation as she and her sister Rosie experienced it. Soon after watching their mother leave, she writes,

Our home clothes were stripped off and we were put in the tub. When we got out we were given new clothes with wide black and white vertical stripes. Much later I discovered that this was almost identical to the prison garb of the time. We were also given numbers. I was 58 and Rosie was 57. Our clothes were all marked in black India ink—our blouses, skirts, socks, underwear, towels, face-cloths—everything except the bedding had our marks on it. Next came the hair cut. Rosie lost her ringlets and we both had hair short over our ears and almost straight across with bangs. Rosie carried me to the lavatory. . . . There were two large mirrors on each end of the room. Susie stopped and let me look at my new self. I started to laugh because I looked so different and my sister looked different too. . . 2

- 1Albert Canadien, From Lishamie (Canada: Gauvin Press, 2012), 50–54. Reproduced by permission of Theytus Books.

- 2Quoted in Isabelle Knockwood, Out of the Depths: The Experiences of Mi’Kmaw Children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia (Lockport: Roseway Publishing, 1994), 28.

Connection Questions

- Describe Albert Canadien’s first day of residential school. What words and images does he use to help the reader understand the experience from his perspective?

- The introduction to this reading includes the word assimilation in quotation marks, asking what “assimilation” looked like in practice. What word or words might Canadien have used instead of assimilation to describe his experience?

- Canadien’s story recounts a series of details about his first day. Why do you think he shares so many of them? What is the point he is trying to convey to the reader?

- How did the teachers in the school seek to change Canadien’s identity? What is lost when one is forced to change his or her identity so violently?

- Why do you think students were forced to go through the sort of drastic physical transformation that Isabelle Knockwood describes? What could be the purpose of the identical clothes they were given? The haircuts? The numbers they received?

- How do you explain why Knockwood laughed when she saw her image in the mirror? What might she have been feeling?

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "First Days," last updated October 16, 2019.