Indian Identities: Mohandas K. Gandhi

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

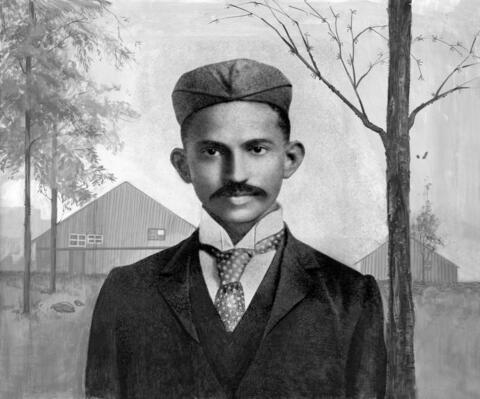

Mohandas K. Gandhi in South Africa, 1895

Mohandas K. Gandhi in South Africa, 1895

In April 1893, Gandhi left India and set sail for South Africa to practice law, spending the next 21 years there. His experiences during this time helped him develop his political and ethical views.

In 1893, Mohandas Gandhi, the future leader of the Indian independence movement, arrived in the city of Durban to work as a lawyer for a large company run by an Indian immigrant to South Africa. Most Indians had come to South Africa as indentured servants to work in the booming sugar industry, an industry that faced constant labor shortages, particularly because the work was punishing. Indians were recruited and arrived in such large numbers that they became one of the four designated racial groups under white race rule. 1 Many white workers began to call for new restrictions on Indian migrants to the region, as the whites feared competition from the growing and successful Indian business population.

It was in South Africa that Gandhi developed his principles and strategies for nonviolent action for social change. The main principles were the pursuit of truth, the use of loving means, and self-sacrifice. Recalling his experience of the social order he encountered soon after his arrival in South Africa and his organizing efforts that followed, Gandhi wrote:

On the seventh or eighth day after my arrival, I left Durban. A first class seat was booked for me . . . But a passenger came . . . and looked me up and down. He saw that I was a "coloured" man. This disturbed him. Out he went and came in again with one or two officials. They all kept quiet, when another official came to me and said, "Come along, you must go to the van compartment." . . .

"But I have a first class ticket," said I.

"That doesn't matter," rejoined the other. "I tell you, you must go to the van compartment. . . . You must leave this compartment, or else I shall have to call a police constable to push you out."

"Yes, you may. I refuse to get out voluntarily."

The constable came. He took me by the hand and pushed me out. My luggage was also taken out. I refused to go to the other compartment and the train steamed away. . . . The railway authorities had taken charge of [my luggage].

It was winter, and winter in the higher regions of South Africa is severely cold. Maritzburg being at a high altitude, the cold was extremely bitter. My over-coat was in my luggage, but I did not dare to ask for it lest I should be insulted again, so I sat and shivered. . . .

I began to think of my duty. Should I fight for my rights or go back to India, or should I go on to Pretoria without minding the insults, and return to India after finishing the case? It would be cowardice to run back to India without fulfilling my obligation. The hardship to which I was subjected is superficial—only a symptom of the deep disease of colour prejudice. I should try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process. . . .

So I decided to take the next available train to Pretoria.

. . . The train reached Charlestown in the morning. There was no railway, in those days, between Charlestown and Johannesburg, but only a stage-coach, which halted at Standerton for the night en route. . . . Passengers had to be accommodated inside the coach, but as I was regarded as a "coolie" [a derogatory term for Indians] and looked a stranger, it would be proper, thought the "leader," as the white man in charge of the coach was called, not to seat me with the white passengers. . . . I could not have forced myself inside, and if I had raised a protest, the coach would have gone off without me. . .

The incident deepened my feeling for the Indian settlers. I discussed with them the advisability of making a test case . . . [M]y mind became more and more occupied with the question as to how this state of things might be improved. . . .

Practice as a lawyer was and remained for me a subordinate occupation. It was necessary that I should concentrate on public work to justify my stay in Natal. The despatch of the petition [to the South African government] . . . was not sufficient in itself. Sustained agitation was essential . . . . For this purpose it was thought necessary to bring into being a permanent organization.

. . . In the same year, 1894, the [white South African] Natal Government sought to impose an annual tax of £25 on the indentured Indians. The proposal astonished me. I put the matter before the Congress for discussion, and it was immediately resolved to organize the necessary opposition.

. . . About the year 1860 the Europeans in Natal, finding that there was considerable scope for sugarcane cultivation, felt themselves in need of labour. Without outside labour the cultivation of cane and the manufacture of sugar were impossible, as the Natal Zulus were not suited to this form of work. The Natal Government therefore corresponded with the Indian Government, and secured their permission to recruit Indian labour. These recruits were to sign an indenture to work in Natal for five years, and at the end of the term they were to be at liberty to settle there . . .

But the Indians gave more than had been expected of them. They grew large quantities of vegetables. They introduced a number of Indian varieties and made it possible to grow the local varieties cheaper. . . . Nor did their enterprise stop at agriculture. They entered trade. . . .

The white traders were alarmed. When they first welcomed the Indian labourers, they had not reckoned with their business skill. . . .

This sowed the seed of the antagonism to Indians. Many other factors contributed to its growth. . . .

We organized a fierce campaign against this [annual] tax. . . . The [Natal Indian] Congress could not regard it as any great achievement to have succeeded in getting the tax reduced from £25 to £3. . . . It ever remained its determination to get the tax remitted, but it was twenty years before the determination was realized. . . .

But truth triumphed in the end. . . . Had the community given up the struggle, had the Congress abandoned the campaign and submitted to the tax as inevitable, the hated impost would have continued to be levied from the indentured Indians until this day, to the eternal shame of the Indians in South Africa and of the whole of India. 2

Connection Questions

- What drove Indian immigration to South Africa? What influenced the racial hostility of whites toward Indians? How did the passenger and the train officials expect Gandhi to respond to their demand that he move? What do their expectations reveal about relationship between racial identity and power in South Africa at the time?

- In response to the injustices he encountered soon after his arrival in South Africa, Gandhi faced a cascading series of choices. What were they? How did each decision lead to the next? In your opinion, what was the biggest and hardest decision Gandhi made that day? How do you see the three principles (which he only later articulated) at work in this story?

- How does Gandhi explain why Zulus, who lived near the sugarcane fields, would not work in them? Are other reasons possible?

- 1By 1911, Indians had become 3% of the population, “coloureds” (people of mixed race) were 9%, whites were 21%, and black South Africans were 67%. (By the 2004 census, the population had shifted, with Indians declining to 2%, coloureds remaining at 9%, the white population dropping to 10%, and the African population increasing to 79%. See “Census in South Africa,” South Africa History Online website, accessed May 24, 2017.

- 2Mahatma Gandhi, Gandhi, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, trans. Mahadev H. Desai (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957), 232–39. Reproduced by permission of The Navajivan Trust.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “Indian Identities: Mohandas K. Gandhi,” last updated July 31, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.