Public Art as a Form of Participation

Overview

About This Lesson

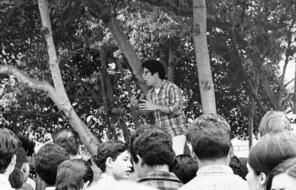

In the last two class periods, students learned about the Battle of Cable Street by listening to and reading first-hand testimonies of individuals who recalled demonstrating against fascist Oswald Mosley and his Blackshirts when they attempted to march into London’s East End on 4th October 1936. In this lesson, students will explore a related story in Cable Street’s history that started in the 1970s when artist Dave Binnington began researching and creating a 3,500 square foot mural on the side of St. Georges Town Hall commemorating the historic Battle of Cable Street and the area’s immigration story. Although Binnington conceived of the mural’s initial design, he abandoned the project in 1982 after it was vandalised with racist slogans, and it was finished in 1983 only to be vandalised again on other occasions in the early 1990s. To introduce this lesson about the artist’s battle to create and preserve the Cable Street mural, students will reflect on the public street art and murals that they may have seen in their own neighbourhoods and schools before doing a close analysis of a large section of the Cable Street mural. They will then read about the mural’s turbulent history, as well as the racism and violence that the East End’s Bengali community has faced since the 1970s and consider how it connects to current racial tension and heightened Islamophobia. The lesson ends with a discussion about the role of art in politics and how art can serve as a means of taking action in the face of injustice.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Activities

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Public Art as a Form of Participation

Standing Up to Hatred on Cable Street

Protesting Discrimination in Bristol

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand