The Housing Clause in the South African Bill of Rights: The Continuing Struggle

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

Winter Floods Affect Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa

Winter Floods Affect Informal Settlement Dwellers in South Africa

A young girl walks home after buying a bottle of paraffin for cooking and heating on June 19, 2016 in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Informal settlements across the Cape Town experienced significant flooding after heavy rainfalls.

The most challenging legacy of apartheid is the vast economic gap between the rich, who historically have been whites, and the poor, who have been and remain mostly black Africans. When the ANC came to power in 1994, expectations were high—no more so than in the area of housing, a basic human need. In 1955, the ANC’s Freedom Charter had boldly declared, “All people shall have the right to live where they choose, be decently housed, and to bring up their families in comfort and security.” 1 But today, over 13% of all South African households live in informal dwellings, such as shacks or shantytowns. 2 Toilets are too few; schools are often absent or inadequate; running water is typically at a communal tap, which may require a long walk to access. Critics have claimed that once the ANC won control of the new government in 1994, too many of its policies focused on middle- and upper-income people, black as well as white.

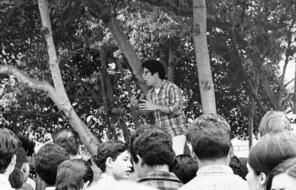

Grassroots organizing has long been a South African tradition and skill. Now housing activism has become a leading movement for the impoverished majority in South Africa. The two documents below chronicle this housing movement, showing both the depth of the need and the organizing being done to meet this need. This first document, in which one South African woman tells her story, comes from a book written and photographed by shack dwellers living along a roadside in Cape Town.

Shamiela Fataar, a 46-year-old single mother of three young children, stands proudly in front of her temporary dwelling along Symphony Way in Cape Town, South Africa. The informal settlement was forcibly disbanded in February 2008.

Shamiela Fataar, “To the Minister of Housing”

The reason why I need a house is I am a 46 year old woman, I have 3 children, and I am a single mother. I am 20 years on the waiting list [for housing]. In the past I was live by sister in Kensington but that was my mothers house. After that, my mother passed away and then the house go over to my older sister. The reason why the house go over to my older sister is because I was married and my husband was the one who was to go to the City and inquire for a house. He passed away in 1994, the same year as Shakira, my daughter, was born. Every time when I go there by the City of Cape Town and ask about my house, they say there is no house. And that was the reason why I come to Delft-Symphony Way.

I am here for a year and two months and on the struggle on the street. I got ill on the street. I am a sick woman, I have epilepsy and arthritis and high blood [pressure]. This effect me a lot. I go for my treatment and my tablets and injections at Sumerset Hospital. I am working for my 3 children. Sometimes I have to struggle for food but why do I need to struggle for a house. A house is for free for everyone.

Everybody must get a house. But why do I have to struggle alone with my children. My one child has [asthma] because of struggling on the road for a house. This is not only for me but for my children. When I pass away then I know my kids is under a roof. Sometimes when [it is] raining, then it is leaking through my hokkie [shack]. Then my house it wet. My beds is getting wet and it is very cold in here. That is the reason we must make a fire to keep us warm.

Ek et nie geweetan struggle nie. I didn’t know the struggle. The reason why I am staying here is that I can feel that I grow up stronger. All the people on this road is not rude with me. We are a happy family here. They support me and is good for me. The struggle for me is now, we all together, standing together and if something happens then we all standing together. Even when the cops come here and try and chase us away, we stand together. The reason I was stay for a long time in hokkies, and that is the reason I want now a house, is so I can feel that I am a mother of the house. I am sick and tired of staying in a hok’.

The struggle has open my mind and open my eyes. You can see what is going on. I know that struggle now because we know we go to the court on the 9th of June and we know that they prosecutor can send us to Blikkiesdorp and we don’t want to go to Blikkiesdorp. 1 A lot of things go on there in Blikkiesdorp. 2

This second document is from the Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement (AbM), a national grassroots organization fighting for the rights of shanty dwellers. Their efforts have led to conflict with the ANC government. Each year, AbM describes its work in a public annual report. The following is an excerpt from the report for 2016.

2016 has been a good year in the movement. Since our movement was formed in 2005 we have been subject to serious repression — including slander, various kinds of dirty tricks, assault, arrest, torture, the destruction of our homes and murder. There has been impunity for this repression which has mostly come from the police and the ruling party [the ANC]. But during this year, as a result of long struggle and building various kinds of alliances, we made a major break through against impunity for repression. Two ANC ward councillors and a hired hit man were sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of Thuli Ndlovu, who was our chairperson in the KwaNdengezi branch. . . .

This was also the year in which we held our elective General Assembly where 28 of our branches, all in good standing, and each represented by 15 members, elected the Provincial and National Council. This was a democratic process where our members elected leaders of their choice. Our movement has always stood for participatory democracy, organised through a system of elected councils, as both a means of struggle and a goal of struggle. We continue to see the building of democratic popular power from below as the form of struggle that will open the road to a more just future in which land and wealth are shared and human dignity is respected.

On the 24th of April this year we held our annual UnFreedom Day event. This event is held every year to contest the idea that freedom arrived for all [on the first day when all could vote] in 1994. Impoverished people continue to be oppressed by an unjust economy, life threatening and undignified living conditions, a lack of access to free quality education, urban planning that works to exclude rather than to include, a form of democracy that is not participatory and repression by the state and the ruling party. Thousands of people attended the event, and for the first time in the history of the movement UnFreedom Day was covered by the SABC [South African Broadcasting Corporation]. . . .

This year also has seen the leadership of the movement kick starting a new round [of] negotiations with the leadership of eThekwini Municipality. These negotiations are still ongoing. . . . But development requires a partnership with government. We entered in these discussions with the municipality purely on the issue of developing our settlements. Also this year on the 17th July the newly elected mayor of the eThekwini Municipality Cllr Zandile Gumede publicly apologised to the membership of the movement for all the wrongs that the ruling party and municipality has caused to the movement in the past. . . .

[W]e still need to fight against our enemies which are capitalism, racism and political gangsterism. We need to unite more than ever before in the new year to fight against these enemies.

Occupy. Resist. Develop. 3

Connection Questions

- Why is Shamiela Fataar in the housing situation she describes? What are the difficulties she has had while living in a shack on the side of a road? What do you think she means by “the struggle”?

- What can people in a democracy do to address economic legacies of the past? What can the government do?

- Why do you think the AbM (housing movement) ends its report with—and thus gives priority to—these three words: occupy, resist, develop?

- What can you learn about the ongoing struggle to address the legacies of apartheid from these two passages on housing rights?

- 1A temporary relocation area built in 2007 with a reputation for being unsafe.

- 2Shamiela Fataar, “To the Minister of Housing,” in (Cape Town: Pambazuka Press, 2011), 28–29. Reproduced by permission of Pambazuka Press with credit to the Symphony Way Pavement Dwellers.

- 3“Abahlali baseMjondolo Movement SA Press statement: 2016: A year of progress for our movement,” Abahali.org, March 23, 2018.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “The Housing Clause in the South African Bill of Rights: The Continuing Struggle,” last updated July 31, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.