The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

- Democracy & Civic Engagement

During the transition, South Africa faced an important question: how to deal with the past and abuses committed under apartheid. As Desmond Tutu, chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and 1984 Nobel Peace Prize winner, warned: “The past has a way of returning to you. It doesn’t go and lie down quietly.”

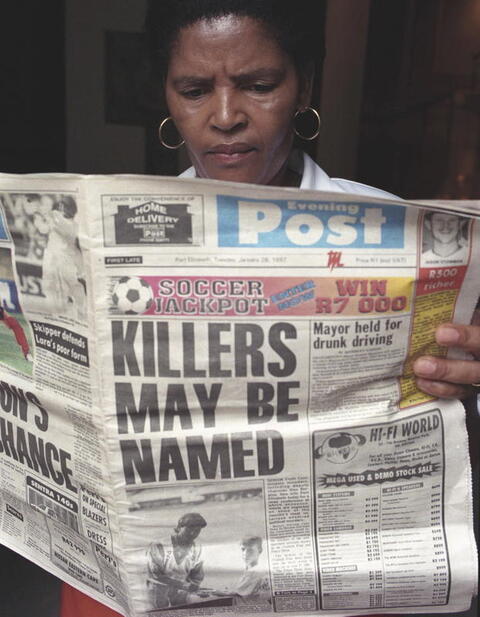

Nomonde Calata Reads the Newspaper

Nomonde Calata Reads the Newspaper

Nomonde Calata, widow of Fort Calata, reads the newspaper to learn the fate of the seven policemen who applied for amnesty for their involvement in the death of Fort Calata at the TRC hearing.

The following document relates to the death of political leader Fort Calata, whom the security police murdered in 1985. Below is the victim statement that his widow, Nomonde Calata, gave to the TRC. At the end of her testimony, she says that she would like to know who killed her husband and why.

MRS CALATA: I am Nomonde Calata, a wife to the late Fort Calata. . . .

The community of Craddock felt that [the new government rent for our housing] was too much for them, because it is a small place and the people were not earning much . . . . Then a meeting was organized to discuss the issue. This is where the committee was elected which was going to handle all this and Matthew [Goniwe, Fort’s friend] was the chairperson of this Committee and Fort was a treasurer . . . This organization then started to become more important. . . .

. . . [T]hings went on and I was arrested in November 1983 . . . [for] wearing a T-shirt on which was printed, “Free Mandela” . . . [Later I was found guilty of wearing that T-shirt and fined a large amount. The next day] [w]hen I arrived at work . . . [they] just dismissed me with immediate effect . . .

MRS. CALATA: On the 27th of June [1985] [Fort] informed me that he and Matthew would be going for a briefing in Port Elizabeth . . . [H]e mentioned when they’ll be coming back because they usually came back at eight . . . So I kept on, I was awake suffering from insomnia. When I looked out, the was a casper [armored vehicle] and vans. The casper was on the other side of the street but not a single car moved around as they usually did. This was also an indication that something was wrong . . . We slept uneasily on Friday as we did not know what happened to our husbands. Usually the [Port Elizabeth] Herald was delivered at home because I was distributing it. During the time that it was delivered I looked at the headlines and one of the children said that he could see that his father’s car was shown in the paper as being burned. At that moment I was trembling because I was afraid of what might have happened to my husband, because I wondered, if his car was burned like this, what might have happened to him? . . . (sobbing)

MR SMITH: Mr Chairman, may I request the Commission to adjourn maybe for a minute, I don’t think the witness is in a condition to continue at the present moment.

CHAIRPERSON: Can we adjourn for 10 minutes please?

OBSERVERS SINGING [a song from the struggle]: What have we done? What have we really done? What have we done?

MRS CALATA: Well of course, I arrived with other women at that place [Mrs. Goniwe’s house]. Mrs. Mkhonto was there with us, Mrs. Goniwe was also there, people were very full in the house, and I learned the news that the bodies of Sparrow Mkhonto, and Mhlawuli have been discovered. I was wondering what happened to Matthew and Fort . . . When I got home, the reverend from my church visited me. He had come to explain that the bodies of Fort and Matthew were found. . . . The community and the family members went out to identify the bodies. Mr. Koluwe, the man we the families asked to go and identify the bodies, has passed away. He said that he had seen the bodies but he discovered that the hair was pulled out, his tongue was very long. His fingers were cut off. He had many wounds in his body. When he looked at his trousers he realised that the dogs had bitten him very severely. He couldn’t believe that the dogs already had their share . . .

MR SMITH: . . . Would you want to know the identity of the person or persons who were responsible for your husband’s death, and if so, why would you like to know who exactly killed your husband?

MRS CALATA: I’d be very glad to know this person. If I can know the individuals who are responsible for this I will be able to understand why they did it. . . . [My children] always ask how he [their father] was and what he will be doing at this time. Tomani, the last born is a child who always wants attention, always wants to be hugged, and even if he’s playing with the other children and talking about the others who always say that their fathers are coming at a certain time, you’ll find that when he comes back he doesn’t know what to say about his father. As a mother I always [have] to play the roles of both parents but I’ll be really glad if I can know what happened so that my children can get an explanation from me, so that I can say it is so and so and so and so. This will probably make me understand. I do not know the reason for their cruelty, but I just want to know and my family will also be happy to know who really cut short the life of my husband. Not to say that when they are old I’m just teaching them to retaliate or be revengeful, it’s just to know who’s done this and who changed our lives so drastically. 1

The second testimony came two years later, when Johan van Zyl, the leader of the police unit that murdered Fort Calata, decided to apply for amnesty. Van Zyl gave this account of killing Fort Calata and three other anti-apartheid activists, who became known as the Cradock Four.

MR VAN ZYL: Colonel Van Rensburg summoned me to his office and told me that the situation at that stage had become so critical that there was only one way in which to try and stabilise these areas, and that was by means of the elimination of Mr Matthew Goniwe and his closest colleagues [including Fort Calata and two others]. . . . Colonel Van Rensburg's words to me were that a drastic plan should be made very quickly with these particular people and that I accepted to mean that they should be eliminated.

MR VAN ZYL: Colonel Van Rensburg . . . informed us [of] that final permission to proceed. Colonel Van Rensburg proposed or gave order that the attack should appear as if it was a vigilante or AZAPO attack [i.e., from the Azanian People’s Organization, an anti-apartheid group]. In other words we should use sharp objects to eliminate the individuals and that we should burn their bodies with petrol. . . . We poured petrol over [their car]. . . . I then gave the order that petrol contained in two petrol cans in my car, be poured over the corpses . . . I can recall that I told them not to forget to remove the handcuffs. The three black members [of the security police] and myself then went back to where Mr Mhlauli's corpse was and I took petrol from the boot of my car, whilst Mr Faku and the other members removed the handcuffs from the body, from the corpse.

CHAIRPERSON [of this hearing]: Whose corpse are you referring to?

MR VAN ZYL: It was Mr Mhlauli's corpse. When Mr Faku [a black policeman] took the petrol from me, they then told me that they could not get the cuffs off the body and that they had to remove his one hand to get the cuffs off.

CHAIRPERSON: You did not see this?

MR VAN ZYL: No, at that stage I was not close to the corpse.

MR VAN ZYL: [I] returned to the city] early in the morning, but it wasn’t light yet. And then for the first time in the light of the parking area, I saw that there was blood on the seat of my car and I washed it off while I was there and then I returned to the office where I arrived at about seven and I reported to Mr Du Plessis that the operation was concluded and Mr Du Plessis and myself went to Captain Snyman's office and we reported to him that the operation was concluded.

ADV BOOYENS [lawyer for van Zyl]: Mr Van Zyl, what you have done, do you agree that this was in contradiction with the laws of the country, did you act on own initiative, did you receive instructions, was this an authorised operation, what is the position?

MR VAN ZYL: I knew strictly speaking that it was an illegal operation, but I knew and I felt that it was an authorised operation . . . . I am applying [for amnesty] because I feel that the crimes in which I participated formed a part of the political struggle of that time. Unfortunate as it was, it was nothing else but that and that is what I base it upon. The facts which I received from Colonel Van Rensburg and later Colonel Snyman personally, are part of that . . .

CROSS-EXAMINATION BY ADVOCATE BIZOS [on behalf of the families of the four activists]: Thank you Mr Chairman. Mr Van Zyl, 63 stab wounds were inflicted on the four people you murdered on the night of the 27th, 1985. Do you agree with the District Surgeon's report with that?

MR VAN ZYL: I cannot disagree with that Mr Chairman.

ADV BIZOS: Do you agree that the 63 stab wounds is evidence of barbaric conduct?

MR VAN ZYL: Mr Chairman, in retrospect, absolutely. The fact is though that instruction was that this killing should look like a vigilante attack and that a more humane way of doing it, would not have had the same effect.

ADV BIZOS: Does your answer mean that you were prepared to behave like a savage barbarian in order to mislead anyone that bothered to investigate the murders that you had committed?

MR VAN ZYL: In effect yes, Mr Chairman. I thought at the time that I could do it and it turned out that I personally was not able to do it myself.

ADV BIZOS: What is it that makes an Officer such as yourself, able to command a Unit that inflicts 63 stab wounds, but you yourself want to have hands supposedly free of blood?

MR VAN ZYL: I was fully intentional to do the whole operation myself at the time, to try and protect the two younger members from the same act. It turned out in the end that I could not do that.

ADV BIZOS: You couldn't stab anybody?

MR VAN ZYL: I have never attempted it, Mr Chairman.

ADV BIZOS: But you could give orders to your black colleagues and supervise their inflicting 63 stab wounds, and you thought that that was better? . . .

CHAIRPERSON: Now, this operation, I am sorry to have to put it this way, but I can think of no other way to put it. Did you enjoy it?

MR J VAN ZYL: No, Mr Chairman. To the contrary.

CHAIRPERSON: Why did you do it?

MR J VAN ZYL: Mr Chairman, I have asked myself that question many times. . . . I think at that time I was just so motivated that I was prepared to do anything for this country. Which in retrospect was misplaced, but I have no other real explanation as that.

CHAIRPERSON: Would these killings have occurred without you being told or ordered to do so?

MR J VAN ZYL: No, Mr Chairman . . .

CHAIRPERSON: You were at liberty to refuse to do so. Is that correct?

MR J VAN ZYL: That’s correct.

CHAIRPERSON: You did not like to do it. Why did you proceed with those orders?

MR J VAN ZYL: Because I agreed that it was probably the only way that we saw at the time to try and stabilise this area.

CHAIRPERSON: What would have happened had you refused?

MR J VAN ZYL: Probably nothing much, Mr Chairman. 2

After deliberations, the TRC rejected Johan van Zyl’s application for amnesty, because the security forces never made a full disclosure regarding the killings. "The commission could therefore not find a relationship between the act and political motives," a TRC spokesperson said. It was a unanimous decision by all three judges and the two panel members." 3

Connection Questions

- What can we learn about both Nomonde Calata’s and Fort Calata’s lives? What was Nomonde hoping to gain by testifying before the commission?

- Nomonde Calata’s testimony immediately appeared in the news media in all the regional languages, including Afrikaans. What did South Africans gain from hearing her testimony? What does her testimony reveal about the TRC?

- What do we learn about the disappearance of Fort Calata and his three colleagues from Johan van Zyl’s testimony? Does his testimony answer Nomonde Calata’s questions?

- What is the significance of the fact that van Zyl’s application for amnesty was rejected by the commission?

- 1Republic of South Africa, ‘Statement by Nomonde Calata to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission” (transcript, April 16, 1996, East London), Department of Justice and Constitutional Development website.

- 2Republic of South Africa, “Truth and Reconciliation Commission Amnesty Hearing” (transcript), Department of Justice and Constitutional Development website.

- 3“No Amnesty for Killers of the Cradock Four,” IOL (Independent Media) website, December 14, 1999.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, “The Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” last updated July 31, 2018.

This reading contains text not authored by Facing History & Ourselves. See footnotes for source information.