Apologies

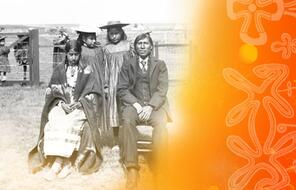

As we have noted, criticism of colonialism and especially the residential schools reached new heights around Canada’s 100th anniversary. The Anglican Church came under scrutiny because of its association with the colonial elites and its role in the residential schools. In 1969, a book written by sociologist George Caldwell criticized, in no uncertain terms, the operation of the nine residential schools in Saskatchewan. This harsh criticism echoed many earlier critiques: Caldwell argued that students who returned from the residential schools to their community could not reconcile the “Euro-Canadian culture they have been socialized into with Aboriginal Culture they now found themselves in.” 1 Neither quite Euro-Canadian nor fully immersed in indigenous culture, they were left to fend for themselves, marginalized, often unemployed, and exposed to a life of crime and alcoholism. 2 The situation, rather than improving, was becoming worse and worse. 3 Despite being the target of widespread criticism, the Anglican Church of Canada failed to respond.

But already things were changing inside the Anglican Church. In 1967 it appointed Charles Hendry to write a report examining directly its residential schools. When Hendry submitted his report in 1969, the church adopted its criticism. Entitled Beyond the Trapline, the Hendry report stated clearly that the Anglican Church’s educational policies of assimilation and conversion “have smashed native culture and social organization.” 4 Moreover, Hendry argued,

The Indians and Eskimo face a total life situation created by two centuries of exploitation, discrimination, paternalism and neglect. They inherited a world their fathers did not make, with no chance of changing it for the benefit of their children. The white conqueror sought his own profit and his own power. The Indians were pushed out of the way. 5

After adopting the Hendry report, the Anglican Church, which was frequently criticized for its cultural arrogance, began to make amends. It increasingly participated in indigenous activism, sided with their land and treaty claims, and contributed to community development efforts. The new critical atmosphere inside the church resulted in greater acceptance of indigenous culture and a growing visibility of indigenous believers in the church. 6

Such attention to the churches’ involvement in the residential schools was part of the growing awareness of globalism, multiculturalism, and pluralism in general. And so, on an ordinary day in 1981, indigenous activist Alberta Billy stood up and told the United Church Executive General Council: “The United Church owes the Native peoples of Canada an apology for what you did to them in residential school.” 7 Jaws dropped, and the stunned members of the council were speechless. But five years later, the Rt. Rev. Robert Smith delivered an apology (see below). The United Church had been formed in 1925 as a union of the Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian Churches. It oversaw the operation of 13 to 15 residential schools, roughly 10% of the total residential schools. In 1986 it made the first of several church apologies.

The government and the major churches, however, remained unmoved. Fearing that an apology would be read as an admission of responsibility and lead to massive lawsuits, they chose to do nothing. The public’s lack of interest or knowledge allowed this continued inaction until a shocking testimony given in October 1990 disrupted the silence. When the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St. Boniface (Manitoba) set up a committee to investigate allegations of sexual misconduct of its clergy, Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Leader Phil Fontaine decided to speak up about his experiences at a residential school in Fort Alexander. 8 On national television, the charismatic, soft-spoken chief reported openly on the information he had given the church authorities in Winnipeg. Facing millions of viewers, he talked about widespread physical, psychological, and sexual abuse in the residential schools and demanded a thorough inquiry. While Fontaine acknowledged that corporal punishment was widely used on many children and youth at the time, he argued that Indigenous Peoples experienced violence on a different level altogether. He and others felt that because clergymen carried out the abuse, it was more than a private matter; it became a socially acceptable norm, sanctioned by the highest authority. 9 When such abuse is made the norm, victims have nobody to complain to and, more importantly, no crime to report, because such behaviour is accepted as normal.

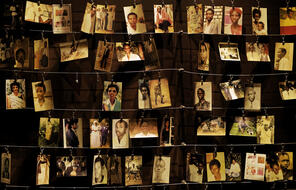

Fontaine’s testimony was not the first time such allegations had surfaced and, of course, the allegations were no secret in private conversations between former students of the residential schools. But this time, the reception was different. The media took notice, and Fontaine’s story was featured in all the major media outlets. 10 A flood of confessions followed, and the stories of many abused students, referred to since as survivors, came to light. The term survivors was borrowed from Holocaust scholarship and was employed to indicate the catastrophic trauma students at the residential schools sustained. 11 Stories of physical punishment, electric shocks, child exploitation, and sexual abuse filled the airwaves, providing ample evidence as to what, until then, had only been rumoured or discussed behind closed doors.

A series of apologies from the different churches involved in the residential schools followed. The Oblate Conference of Canada issued a public apology in 1991, limited to the “1200 Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate living and ministering in Canada.” 12 Two years later, in 1993, the then Primate of the Anglican Church, Michael Peers, delivered that church’s apology in front of the National Native Convocation in Minaki, Ontario. Following the Anglican apology, the Presbyterian Church delivered one in 1994, and the United Church did so in 1998. Finally, in April 2009, Phil Fontaine, who was then leader of the Assembly of First Nations, accepted an invitation from Pope Benedict XVI to receive an official apology from the Vatican. Following the meeting, the pope released a statement saying that “the Holy Father expressed his sorrow at the anguish caused by the deplorable conduct of some members of the Church and he offered his sympathy and prayerful solidarity.” 13 Many indigenous survivors continue to hope that the Catholic Church would provide a more thorough apology, though some dioceses are deeply engaged with indigenous communities in work of reconciliation and forgiveness. 14

- 1Quoted in Eric Taylor Woods, The Anglican Church of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, 113; see also James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision, 2009), 386.

- 2George Caldwell, “An Island Between Two Cultures: The Residential Indian School,” Canadian Welfare, July-August, 1967, 12–17.

- 3ohn Milloy, “Indian Act Colonialism: A Century of Dishonour, 1869-1969,” National Centre for First Nations Governance, 2008, accessed May 8, 2015.

- 4William J. Danaher, “Beyond Imagination: ‘Mutual Responsibility and Interdependence in the Body of Christ’ (1963) and the Reinvention of Canadian Anglicanism,” Anglican Theological Review 93, no. 2 (Spring 2011), 239–240.

- 5Quoted in Eric Taylor Woods, The Anglican Church of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, 119.

- treatytreaty: A treaty is a legally binding agreement between two sovereign nations. In Canada, various treaties between First Nations and the British Crown have been signed over the decades. The intent of many treaty agreements was to initiate a system in which First Nations peoples would share the land with the settler society but retain their autonomy and inherent rights to land and resources.

- 6Quoted in Eric Taylor Woods, The Anglican Church of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, 104–105.

- 7Martha Troian, “25 Years Later: The United Church of Canada’s Apology to Aboriginal Peoples,” Indian Country Today Media Network.

- 8Woods, The Anglican Church of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools, 72–75.

- 9“Phil Fontaine’s Shocking Testimony of Sexual Abuse,” CBC Digital Archives, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 10“Phil Fontaine’s Shocking Testimony of Sexual Abuse,” CBC Digital Archives, accessed September 11, 2014.

- survivorssurvivors: The term survivors was first used to refer to individuals who lived through the Holocaust and other genocides; many believe residential school students share similar symptoms with other survivors, including emotional detachment, guilt, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. First used in the 1990s in the discussion of the experiences of indigenous students in the residential schools system, the term also refers to former students of these schools, individuals who suffered neglect and physical and sexual abuse at the hands of their supposed teachers and instructors.

- 11Ronald Niezen, Truth and Indignation: Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Indian Residential Schools (Toronto: UTP Ethnographies for the Classroom, 2013), Kindle Locations 545–571.

- 12“An Apology to the First Nations of Canada by The Oblate Conference of Canada,” Speaking My Truth website, accessed September 11, 2014. Reproduced by permission of Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- 13“The Residential School System,” UBC Indigenous Foundations website, accessed September 11, 2014.

- 14Per Commissioner Marie Wilson, private communication.