Banning Indigenous Culture

The government’s aim, however, was even farther-reaching. It did not seek only to rearrange indigenous communities from within. It wanted all indigenous people in Canada to become “enfranchised,” effectively destroying indigenous nations as distinct groups. “In the period in which the British imperial government was responsible for Indian affairs from 1763 to 1860,” writes John S. Milloy, a prominent residential schools historian, “Indian tribes were, de facto, self-governing.” 1 But now things shifted. Already, in 1857, “a wholly new course was charted. Thereafter, the goal, full civilization [of the Indian], would be marked by the disappearance of those communities as individuals were enfranchised and the reserves were eroded, twenty hectares by twenty hectares.” 2 As Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald said in 1887, after the residential schools began to operate, “The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change.” 3 Yet despite this high talk of Indian enfranchisement, the official process designed to assimilate indigenous people as soon as possible, Indigenous Peoples in Canada could not vote until the 1960s.

- 1John Milloy, “The Early Indian Acts: Developmental Strategy and Constitutional Change,” in As Long as the Sun Shines and Water Flows, 57.

- 2John Milloy, “The Early Indian Acts: Developmental Strategy and Constitutional Change,” in As Long as the Sun Shines and Water Flows, 59.Sessional Papers, vol. 20b, Session of the 6th Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, 1887, 37.

- 3Sessional Papers, vol. 20b, Session of the 6th Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, 1887, 37.

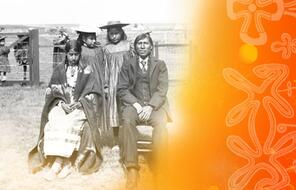

Men celebrate the sun dance, an annual ceremony practiced traditionally by Indigenous groups from the Plains, at the Blood Indian Reserve in Alberta. An amendment passed in 1885 to the Indian Act forbade the practice of this ceremony.

Today, Canada prides itself on being a multicultural society, an “ethnic mosaic,” in which people of different backgrounds and heritages are able to live together without losing their distinct identities. This is often set against the analogous idea in the United States, where people have historically talked about a “melting pot”—a metaphor for the blending of diverse ethnic and religious identities. Critics suggest, however, that Canada’s policies with respect to the Indigenous Peoples within its borders contradict the idea of protecting the separate identities of minorities under one national umbrella. The key issue is that, properly speaking, First Peoples in Canada are not minorities—they have distinct legal and historical relations with the Crown that define them as autonomous nations. The ultimate goal of the Indian Act has always been the assimilation of the Indigenous Peoples as separate nations into mainstream Canada.

For example, to further remove the beliefs, values, and principles at the heart of indigenous identities, the Indian Act suppressed expressions of indigenous culture such as traditional ceremonies, including the sun dance and, in particular, the potlatch. 1 Europeans regarded these ceremonies as part of a primitive world of superstitions, myth, and magic. Thus Catholic and Protestant missionaries strove to ban them altogether. The discrimination against the ceremonies and greater indigenous cultures was transmitted through legislation, as well. The ceremonies were condemned because they conflicted with the ways of European business, which encouraged frugality, savings, and an exact exchange of goods for money. Not until 1951 did an amendment to the Indian Act remove sections that restricted customs and culture. We should note that while government officials and clergy outlawed sacred objects, totem poles, masks, pipes, and the like, many of those same officials and clergy collected them privately, and often sold them at lucrative prices. 2

- 1For example, the potlatch, a vital part of the Pacific Northwest First Nations culture, was banned from 1884 until 1951. For a classic description of the potlatch and its significance at the turn of the century, see Franz Boas, “The Potlatch,” in Tom McFeat, ed., Indians of the North Pacific Coast (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1966), 72–80.

- 2Stacey Jessiman, “Cultural Heritage Repatriation as a Means of Restorative Justice, Affirmation and Cultural Revival for Aboriginal Peoples in Canada,” paper presented at the International Association of Genocide Scholars conference, “Time, Movement, and Space: Genocide Studies and Indigenous Peoples,” July 16–19, 2014, University of Winnipeg.