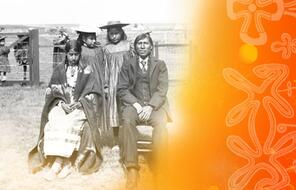

Building the Indian Residential Schools System

From 1883 onward, the federal government sought a system to enroll indigenous children in schools. Day schools and industrial schools were to serve alongside the residential schools to meet this growing challenge. One of the most important historians of the residential schools, James R. Miller, estimates that a great number of indigenous students were, in fact, educated in day schools, although the residential schools left the most painful, long-lasting marks on indigenous communities. Day schools, too, were operated by municipal authorities and the churches and attempted to reach the same goals. As a result, many of the troubles and abuses found in the residential schools were also found in the day schools. 1

The government began with a modest budget of $44,000 a year in 1883. This money, however, came mostly from cuts to government spending on other indigenous needs. Historians claim that these cuts indicate the government’s limited commitment to investing in the program—financially and otherwise—from the beginning. Despite its talk about the urgent need to civilize Indigenous Peoples, the government was determined to educate them on the cheap, relying heavily on the churches and their supporters to chip in. 2 Since much of the financial burden fell on the local schools, they tried to shift the costs to the parents, often with little success. Most schools used the children in their care to make clothes, grow vegetables, plant trees, raise animals for food, and perform chores necessary for the daily operation of the schools.

As the system grew, so did Ottawa’s fears that it was becoming too costly. As early as 1892, barely four years into the plan, the government switched to a new financial system in which the schools received a fixed allowance for every student they had (a per-capita grant). In a short time, schools that were not already struggling began to feel the pinch, and many began to run a significant deficit. This was bad news for all involved—there wasn’t enough money to make repairs, to hire enough staff, to pay adequate salaries, or to properly feed the students. 3

The immediate result was increased pressure to use student labour to provide goods, food, and services. Moreover, once the per-capita system was in place, schools fought to recruit as many students as they could to increase their grants. Schools were now competing with each other for new students (even as late as the 1950s)—often “stealing” students from one another—since the more students they had, the more money they got. These conflicts increased the suspicions in indigenous communities, adding to concerns that the schools did not meet basic academic standards. 4 Many parents now simply refused to send their children to church-run institutions. Against this backdrop, the majority in the indigenous communities felt that the schools violated their rights and expectations and that the government was taking their children by force.

At about the turn of the twentieth century, some government officials also became aware that the schools were not meeting their goals. Evidence of just how neglectful and dangerous the schools were for the students began to pile up: reports of dilapidated buildings, shortages of fuel for heating, poor and insufficient diet, unsanitary living conditions, widespread illness, and, above all, the general unhappiness of indigenous students. Academically, the picture was not much different and, in fact, reflected the overall failing of the residential school project: historian James R. Miller has summarized the situation by saying that “the whole system had been declining into a uniform mediocrity.” 5 The government provided little leadership, and the clergy in charge were left to decide what to teach and how to teach it. Their priority was to impart the teachings of their church or order—not to provide a good education that could help students in their post-graduation lives. 6 Moreover, the distinction between industrial and residential schools was fading amid criticism that neither achieved much in the way of teaching meaningful skills or trades. Finally, in 1923, this nominal distinction was abolished and both institutions became residential schools.

First Nations were a prime target of the Indian Residential Schools, the education system this guide explores in detail. For years, they made up the majority of the populations subjected to these schools. For the Inuit, residential schools began much later than in other parts of Canada. For decades, the government chose not to address the economic and social challenges facing the Inuit people. When it did so, it implemented the same educational policy it had implemented elsewhere. It was not until 1951, when the first school opened in Chesterfield Inlet, that the Canadian government became more involved. With declining income from fur and fishing, the government feared the Inuit people would require state assistance. As a result, it started to force Inuit children into residential schools or hostels, which were smaller student residences. 7 Western education, the government believed, would help the Inuit help themselves. By June 1964, under growing pressure and threats from the government, nearly 4,000 Inuit children, or 75% of youths aged 6 to 15, were attending residential schools. 8

The vast distances between communities in the region added to what was, anyway, a tragic experience for most attendees of residential schools. In the most glaring example, in the Arctic and Sub-arctic regions, students were taken from their families, flown hundreds of kilometres away, and were hardly ever able to see their parents again.

The schools also treated Métis students differently. Generally speaking, because the government did not give the Métis Status Indian recognition, fewer were enrolled in residential schools (the schools were part of the protection the government extended to those it defined as Status Indians). Even so, many Métis did end up in the residential schools. As the authors of Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada explain:

Many so-called half-breeds, particularly those residing on or near reserves, attended industrial and boarding schools until 1910. A new agreement was then negotiated between the churches and the Department of Indian Affairs. The agreement specified that only children belonging to Indian bands could attend residential schools and management was to disallow ‘the entrance of half-breed children into the Boarding Schools unless Indian children could not be obtained.’ The Department of Indian Affairs stipulated that it would not pay a grant or any part of the maintenance or education costs of any half-breed children admitted to the schools. As a result, those Métis allowed to enter the schools did so as objects of charity of the churches because few parents were able to pay the fees. Some Métis were in attendance in almost every school. 9

One reason for their presence in residential schools was the government effort to address the perception of widespread poverty in indigenous communities. In the 1960s, the government removed as many as 20,000 children from indigenous parents, supposedly as a form of welfare. Patrick Johnston, in a 1983 report titled Native Children and the Child Welfare System, coined the term Sixties Scoop to describe this widespread practice. These “scooped-up” kids were sent away to foster families, who were often not better suited to care for them, and many ended up in residential schools. 10 Others were moved to the United States for adoption.

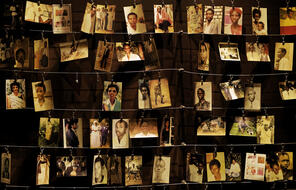

Over the years, as a result of neglect and funding shortages, the residential schools saw many casualties. Students lived in crowded dormitories and were rarely isolated when sick, which made the schools prone to outbreaks of diseases, most notably tuberculosis and the flu (the “Spanish flu” epidemic of 1918 hit residential schools especially hard). So far, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has confirmed the deaths of more than 6,000 children, with potentially many more yet to be counted. And as evidence of neglect and abuse piles up, it becomes clear that many of these children did not die of disease or natural causes. 11

Some of these issues were known early on and were readily ignored. For example, Dr. Peter H. Bryce, who was a medical inspector for the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) in the early 1900s, investigated and reported on the conditions in the residential schools on the Prairies, and his findings were ignored if not outright rejected. He discovered that the health conditions were so appalling and the level of tuberculosis infection so high “as to jeopardize the health of the western Indians in general.” 12 In his 1907 report, Bryce argued that of the students in the schools he surveyed, “7 per cent are sick or in poor health and 24 per cent are reported dead.” He cited lack of ventilation and overheating as the main reasons for the widespread sickness in the residential schools. 13 In response to the criticism of Bryce and his collaborators, in 1909 the DIA appointed Duncan Campbell Scott to head Indian education.

- 1 “Residential School Locations,” Truth and Reconciliation Commission website, accessed June 18, 2015.

- 2James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 125.

- 3Donald J. Auger, Indian Residential Schools in Ontario, 15.

- 4James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 135.

- 5James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 135.

- 6P. Raibmon, “A new understanding of things Indian: George Raley’s negotiation of the residential school experience,” BC Studies no. 110 (Summer 1996), 72.

- 7Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children, 56.

- 8“Residential Schools,” Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada website, accessed March 5, 2015.

- 9Larry N. Chartrand, Tricia E. Logan, and Judy D. Daniels, Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada (Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2006), 33.

- 10Margaret Philp, “The Land of Lost Children,” The Globe and Mail, December 21, 2002, accessed September 10, 2014.

- 11Jorge Barrera, “Truth and Reconciliation Commission Piecing Fragments from History’s Shadows to Find the Missing Children,” APTN National News website, March 29, 2014, accessed September 30, 2014.

- 12James R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009),134.

- 13Peter Henderson Bryce, Report on the Indian schools of Manitoba and the North-West Territories (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1907), 18. Dr. Bryce (1853–1932) served as the chief medical officer for the Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs.